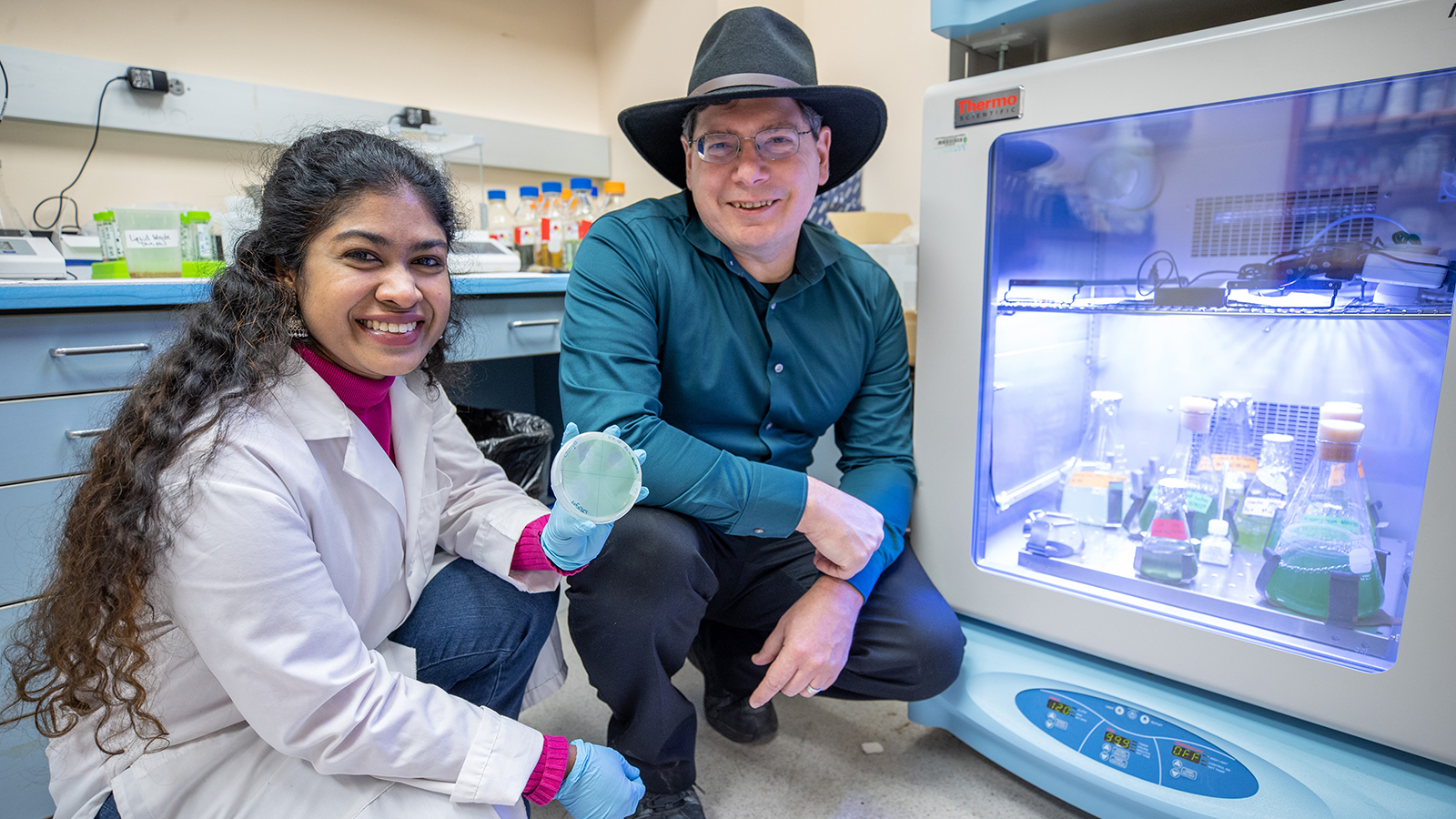

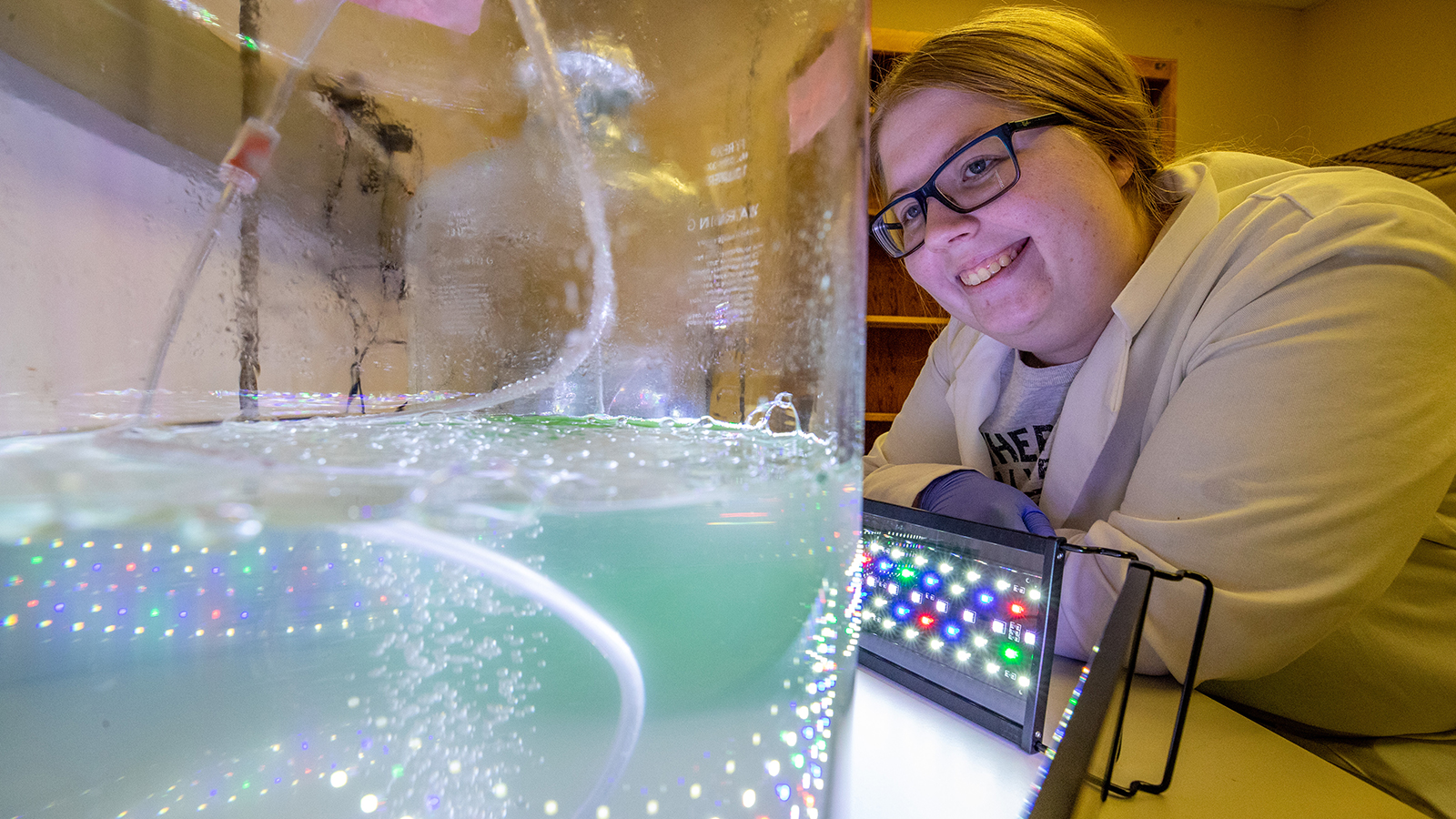

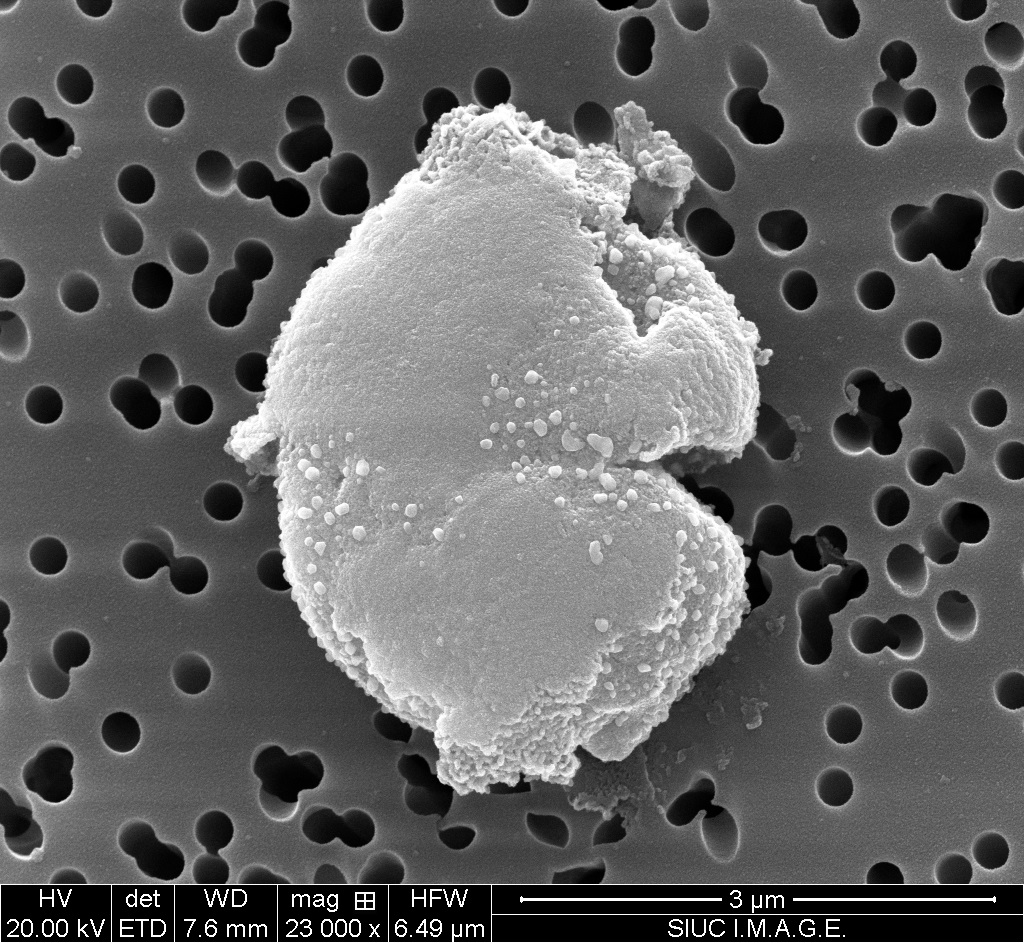

(Top) SIU doctoral student Sandhya Jayasekara and Associate Professor Scott Hamilton-Brehm show off an agar plate with Microcystis aeruginosa, a type of cyanobacteria, that has clearing zones showing they are being shut down and killed from the team’s process. In the orbital shaker next to them are liquid cultures of the different strains of M. aeruginosa. (Middle) Master’s student Bethany Egge watches her large-scale culture of M. aeruginosa growing under controlled environmental conditions with LED lights imitating sunlight. (Bottom) An M. aeruginosa cell is deteriorating 24 hours after receiving the molecular message delivered by the transporter. (First two photos by Russell Bailey, third photo courtesy of Scott Hamilton-Brehm)

January 08, 2026

SIU team gets $170K grant to continue research to stop toxins from harmful algae blooms

CARBONDALE, Ill. – A research team at Southern Illinois University Carbondale has received a second grant to continue its work to prevent harmful algae blooms from producing toxins, addressing a problem that occurs in bodies of water throughout the world. In this phase of the project, the team will investigate whether they can scale up the technology and measure its impact on the environment and the food web.

The team led by Scott Hamilton-Brehm, an associate professor in SIU’s School of Biological Sciences, received $170,000 from U.S. Harmful Algal Bloom Control Technologies Incubator, a partnership among the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), the University of Maryland’s Institute of Marine and Environmental Technology and Mote Marine Laboratory. This is in addition to the $220,000 the group received to start the project in 2023.

Cyanobacteria, aka blue-green algae, are harmless in themselves, but they can become harmful algae blooms (HABs) when they grow into high concentrations in freshwater or saltwater environments, producing a toxin that damages the livers of mammals, including wild animals, livestock, pets and humans. Killing an HAB is not that simple – as cyanobacteria cells are killed, they release all of their toxin into the water.

“Every year millions, if not billions, of dollars in recreational and health damage are caused by these microbes,” Hamilton-Brehm said. “There currently is no viable means of controlling them. If we are successful, controlling them will be as simple as loading up a crop duster and spraying ponds, lakes and rivers to stop the toxin production.”

In 2020, Hamilton-Brehm and Marjorie Brooks (now a retired associate professor in the School of Biological Sciences) mentored a graduate student who confirmed that a molecular message could be put into cyanobacterial cells to tell them to stop making the toxin during an algal bloom.

“But we needed develop a ‘transporter’ to get the message to the cells,” Hamilton-Brehm said.

For the first federal grant, Hamilton-Brehm and Brooks partnered with Lahiru Jayakody, associate professor in SIU’s School of Biological Sciences and the Fermentation Science Institute, to do the synthetic biology needed to make the molecular “transporter.” Initial results are promising, and the team has filed a U.S. provisional patent application (63/930,143).

“In the lab, we have already shown we can knock down about 40% of the toxin in an HAB,” Hamilton-Brehm said.

The next steps involve three labs. Hamilton-Brehm’s team, which includes master’s student Bethany Egge and fourth-year undergraduate Hannah Phillips, will test the technology on 5- and 10-gallon aquariums and analyze results overall. Jayakody’s team, which includes doctoral students Sandhya Jayasekara and Bhagya Jayantha, will continue to perfect the “transporters.” Now, Brooks is working with Charlotte Narr, an assistant professor in Biological Sciences, and her team to test whether the technology affects the food web. They will use daphnia. The tiny crustaceans, also called water fleas, eat cyanobacteria and algae and are in turn eaten by fish, amphibians and insects (an example of the food web).

The next steps involve three labs. Hamilton-Brehm’s team, which includes master’s student Bethany Egge and fourth-year undergraduate Hannah Phillips, will test the technology on 5- and 10-gallon aquariums and analyze results overall. Jayakody’s team, which includes doctoral students Sandhya Jayasekara and Bhagya Jayantha, will continue to perfect the “transporters.” Now, Brooks is working with Charlotte Narr, an assistant professor in Biological Sciences, and her team to test whether the technology affects the food web. They will use daphnia. The tiny crustaceans, also called water fleas, eat cyanobacteria and algae and are in turn eaten by fish, amphibians and insects (an example of the food web).

“Dr. Narr’s team will see: If we were to use this technology in the wild, would it cause any unwanted harm?” Hamilton-Brehm said. “So far, the answer seems to be no.”

(Note to editors: Additional photos are available upon request. Scott Hamilton-Brehm’s last name is pronounced Ham-ill-ton-Breem. Lahiru Jayakody’s name is pronounced La-HIGH-roo JAY-ya-kody.)