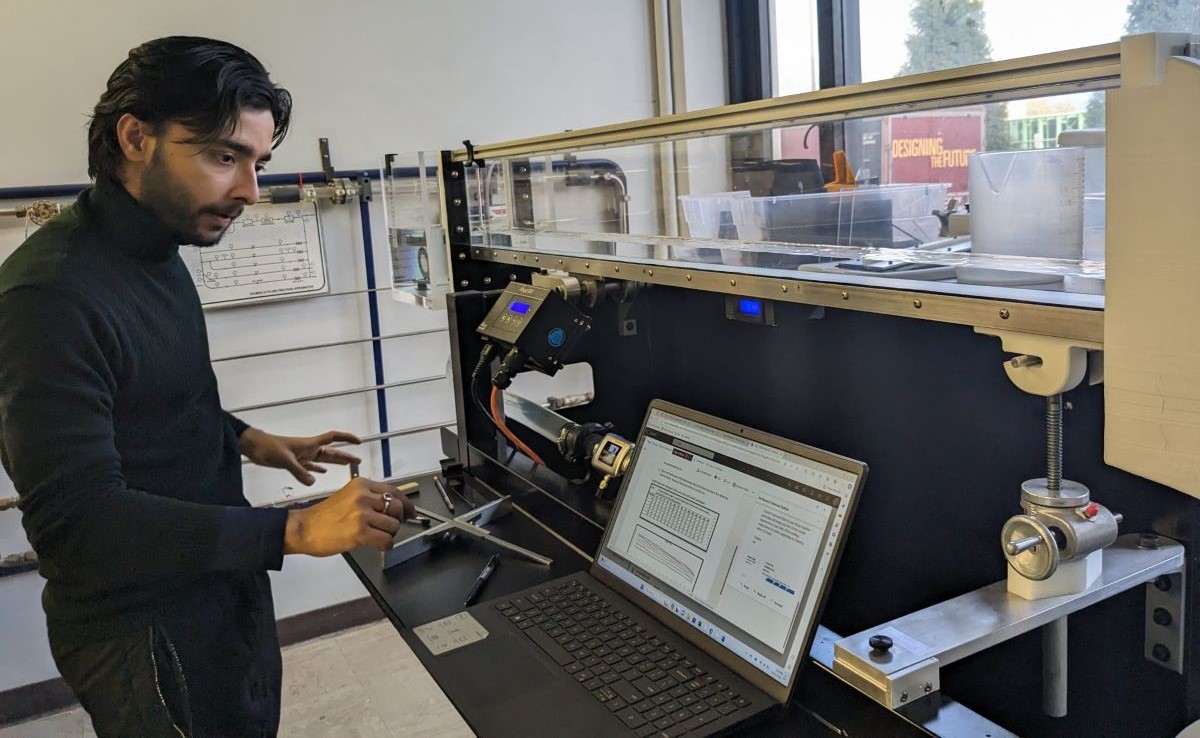

(Above) Dewasis Dahal works in an SIU lab to calibrate hydraulic experiments using a flume from Little River Research & Design. (Photo courtesy of Little River Research & Design). Dahal does fieldwork at a lake few miles south of the SIU campus (middle photo) and in Nepal (bottom photo). (Fieldwork images courtesy of Dewasis Dahal)

January 07, 2026

SIU grad engineers solutions to protect communities from water-related disasters

CARBONDALE, Ill. — Growing up in Nepal’s flood-prone Terai region, Southern Illinois University Carbondale graduate Dewasis Dahal learned early that water can be both a lifeline and a threat. Monsoons make crops possible and refill wells. But on trips with his father — an executive at a nonprofit that supports community projects — Dahal also saw the other side of that seasonal rhythm: floods and landslides that uprooted families, damaged roads and bridges, and left rural communities without safe drinking water. Those moments planted a question that has stayed with him ever since: How can engineering help communities not just recover from water-related disasters, but adapt and prepare for what comes next?

When Dahal arrived at SIU in August 2023 to pursue a master’s degree in civil engineering, he quickly caught the attention of Associate Professor Ajay Kalra. “He stood out as a hard-working, curious student who was eager to learn and contribute,” Kalra recalled. After taking Kalra’s courses in open-channel hydraulics and water resources engineering, Dahal joined the professor’s Water Resources Lab — and soon built a research record that is rare for a master’s student, publishing more than 10 peer-reviewed journal articles, including four as lead author.

Much of Dahal’s research centers on using artificial intelligence and machine learning to improve flood prediction. Water problems often involve massive datasets — decades of rainfall records, soil moisture, land-use change and river discharge measured at fine time scales. “Traditional methods alone struggle to capture the complexity,” he said; machine learning can help identify patterns “that would otherwise be difficult to detect.”

Because his graduate research was done with tight budgets, Dahal became deliberate about choosing approaches others could use. He leaned on openly available data and efficient tools and focused on methods that can be implemented without expensive software or equipment. “If a method is too costly or complex, it often stays on paper,” he said. Designing low-cost, practical solutions became a core goal — so research can move beyond academia and make a difference on the ground.

“Behind every dataset or model are real lives and real challenges,” he said, and that mindset pushes him to ask better questions — and stay focused on why the work matters.

For one of his projects, Dahal analyzed climate dynamics and developed machine-learning models to improve flood forecasting in Sacramento, California — among the nation’s most flood-prone regions. Published in Hydroecology and Engineering, the research also earned the Top Poster Award at SIU’s spring Creative Activities and Research Presentations, sponsored by the Office of the Vice Chancellor for Research.

“Dewasis’ work reflects exactly what we aim to develop at SIU: a balance between theory, modeling and application,” Kalra said. He added that SIU trains students to tackle applied problems, collaborate closely with faculty and peers, “and learn by doing — not only by theory.” That kind of environment, Kalra noted, prepares engineers to take on complex, fast-changing challenges like climate variability, flood risk and urban water management with both rigor and responsibility.

Research with real-world stakes

At Kathmandu University, where he earned a bachelor’s in environmental engineering, Dahal learned that water management isn’t only technical — it connects directly to equity, safety and quality of life. His bachelor’s thesis examined Nepal’s first centralized wastewater treatment plant through a life-cycle assessment — work that could inform future plant design and policy decisions. Realizing the research might shape real infrastructure choices, he said, was “deeply meaningful.”

Dahal chose to advance his education at SIU Carbondale, attracted by its focused, welcoming environment and a full scholarship that allowed him to devote himself to graduate study. The transition to an American university was eased by support that began even before he arrived: Future lab mates helped with housing and logistics, and faculty checked in regularly.

Inside Kalra’s Water Resources Lab, Dahal found a culture built on collaboration and applied problem-solving. The lab is “highly diverse,” he said, and emphasizes “working on real problems rather than only theoretical exercises.”

SIU’s emphasis on connecting learning to practice extended beyond the lab. Dahal researched flood mitigation and low-impact development strategies in the American Bottoms and East St. Louis — communities facing long-standing environmental and social challenges. The work explored how green infrastructure such as permeable pavement, bioswales and green roofs can reduce urban flooding while improving water quality. “Projects like this showed me how technical analysis, when guided by purpose, can directly connect to people’s lives,” Dahal said.

Dahal also interned with the Illinois Department of Transportation’s District 9 utilities team, gaining field experience, and collaborated with Carbondale-based Emriver Inc. to help calibrate hydraulic flumes used for education and research.

Engineering meets equity — and creativity

That practical focus is matched by an ethical one. Dahal’s early experiences in Nepal shaped a belief that vulnerable communities are often hit hardest by water-related disasters while having the least influence in planning and decision-making. “If engineering solutions don’t reach the people who face the highest risks, then they aren’t truly solving the problem,” he said.

Colleagues describe Dahal as “a poet at heart and an engineer by training,” a characterization he embraces. He has performed slam poetry as a hobby, and he believes creativity helps him step back and view technical work through the perspective of the people affected.

Dahal credits Kalra with helping him build the confidence to become a published scholar and to think like an independent researcher. He recalls Kalra’s guiding philosophy: “I will be successful when my students are successful.” That support and willingness to give students independence, Dahal said, made it easier to take on ambitious projects and strengthen scientific arguments.

Kalra sees Dahal’s growth as a case study in what the field now demands. With climate variability increasing both flood and drought risk, and with urban sustainability requiring better water planning, engineers must be comfortable crossing traditional boundaries and working with uncertainty. Dahal, he said, learned to blend fundamental hydrology with modern data-driven approaches while staying grounded in real systems and real communities.

From campus to community impact

After completing his SIU coursework last spring, Dahal now applies those skills as a water resources engineer at Illinois-based Maurer-Stutz, working on projects such as two-dimensional hydraulic modeling to evaluate infrastructure and reduce flood impacts, and dam-breach analyses that support emergency planning. A December 2025 graduate, he sees that work as a continuation of the mission that drew him to the field: using engineering to protect communities as water risks grow more unpredictable.

“Many of the world’s biggest challenges, like water, climate and energy, are still unsolved,” he said. “Even small efforts, when guided by care and purpose, can lead to meaningful change.”