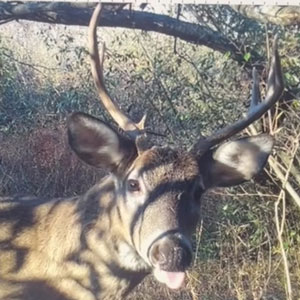

John Vinson, a postdoctoral associate at the Center for Wildlife Sustainability Research, and Nina Davis, an undergraduate in zoology, are two of the SIU researchers studying deer interactions at Touch of Nature Outdoor Education Center in an effort to slow the spread of chronic wasting disease. The study used video cameras to take hundreds of hours of images like the one below. (Photo by Russell Bailey)

April 15, 2025

SIU researchers study social lives of deer to prevent spread of fatal illness

CARBONDALE, Ill. – Wildlife researchers at Southern Illinois University Carbondale are using cameras to take a closer look at how deer socialize to better understand how a deadly disease is spread.

Working with the deer population at SIU’s Touch of Nature Outdoor Education Center, John Vinson, a postdoctoral associate at the Center for Wildlife Sustainability Research, assisted in an effort in 2023 to capture and camera-collar 20 of them. Then, in 2024, Vinson along with about 10 zoology students began analyzing the nearly 70,000, 15-second videos, totaling around 300 hours of screentime.

The work, which also included Guillaume Bastille-Rousseau, assistant professor of zoology at the CWSR, was done in cooperation with the U.S. Department of Agriculture and Illinois Department of Natural Resources and may lead to better wildlife management techniques to slow chronic wasting disease spread among local deer populations. This project is one example of why SIU Carbondale is a Research 1 university in the Carnegie Classifications of Institutions of Higher Education.

The researchers are using a major portion of the video to help build a transmission model for chronic wasting disease, a fatal brain disease affecting hoofed mammals and particularly white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus). With the majority of transmission happening in the northern parts of Illinois, understanding how contacts among deer occur and how the disease may change will be crucial to mitigating and managing its impact, Vinson said.

“We are also interested in looking at how these contacts and interactions may vary through time,” Vinson said. “These collars were on the deer for a year, so we can see if they are doing more risky interactions at different times of the year or even if they are having more contacts at different times of the year.”

Massive data

Analyzing the videos required the team to view each one in detail to determine what the deer was doing, where the deer was located and whether any other deer were nearby at the time. Reviewing the sheer amount of video created by the study was daunting, Vinson said, as every single video needed scrutiny.

“I generally gave students sets of 1,000 videos at a time, and there was an almost constant flow of getting back analyzed videos and giving out new sets,” Vinson said. “This lasted for about five months.”

He also ensured all videos were analyzed using the same methods and criteria, to maintain scientific standards. This required him to establish a protocol with examples.

“I sat down with each student and walked them through the protocol and some videos so they would be comfortable and confident when they worked on their own,” he said. “With still images you never get the full story. The camera is stuck in one place; it doesn't follow individuals around and show what they’re doing. Videos allow us to get longer, more detailed glimpses into an individual’s life. We get to see exactly what they’re doing, what they’re seeing, who and what they’re interacting with.”

Social behaviors key

One of the ways that CWD, also called zombie deer disease, is contracted is through direct contact with an infectious individual. Therefore, learning more about how deer socialize is a high priority for the researchers. In viewing the video, the researchers noted interaction between two or more deer that are risky for CWD transmission, and others that are not so much, such as just occupying the same space but not really coming close to each other. The videos also provided researchers with unexpected insights into deer behavior.

One of the ways that CWD, also called zombie deer disease, is contracted is through direct contact with an infectious individual. Therefore, learning more about how deer socialize is a high priority for the researchers. In viewing the video, the researchers noted interaction between two or more deer that are risky for CWD transmission, and others that are not so much, such as just occupying the same space but not really coming close to each other. The videos also provided researchers with unexpected insights into deer behavior.

“I've seen some pretty interesting things, from nursing of a fawn on a collared doe, to fighting between two bucks in a group and even the end of a life of an individual that ended up getting scavenged on by a bird,” Vinson said. “This is all stuff I never got to work with in my previous projects, so it's all pretty interesting to me.”

Students heavily involved

Nina Davis, a wildlife research assistant and undergraduate student, concentrated on deer behavior and habitat analysis. She analyzed the video, categorizing them by deer location and behavior. She also identified and recorded the number of other deer present in each video, closely observing their interactions.

Davis said she learned about the movement patterns, social interactions and habitat use of deer, noting how they interrelate in different environmental contexts. The experience helped sharpen her ability to distinguish between subtle behavioral cues in free-roaming deer, she said. It also expanded her skills in analyzing animal interactions, which will be beneficial as she explores such areas as predator-prey dynamics and the effects of intraspecific relationships in future studies, and many other areas in animal behavior.