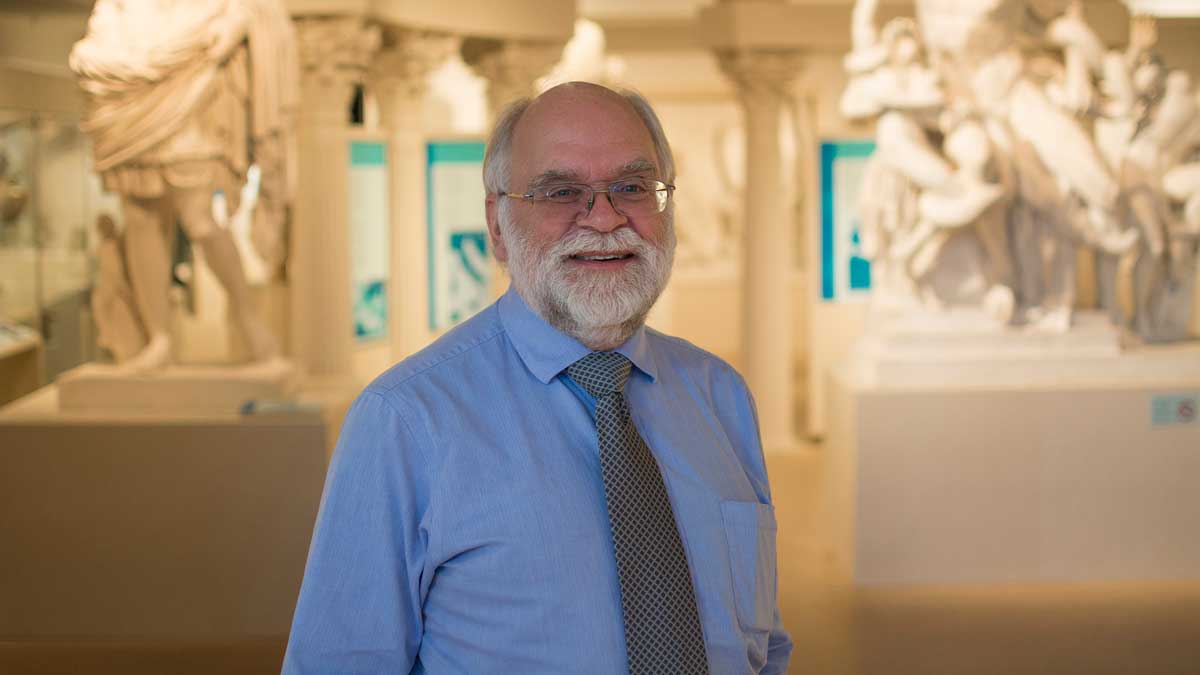

Wayne T. Pitard is the recipient of the 2024 Delta Award by SIU Carbondale’s Friends of Morris Library for his book on John J. Bird, a highly respected civil rights, political and education leader, who lived in both Cairo and Springfield. (Photo by Spurlock Museum of World Cultures)

November 01, 2024

Book about forgotten Black leader in Illinois wins SIU’s Friends of Morris Library Delta Award

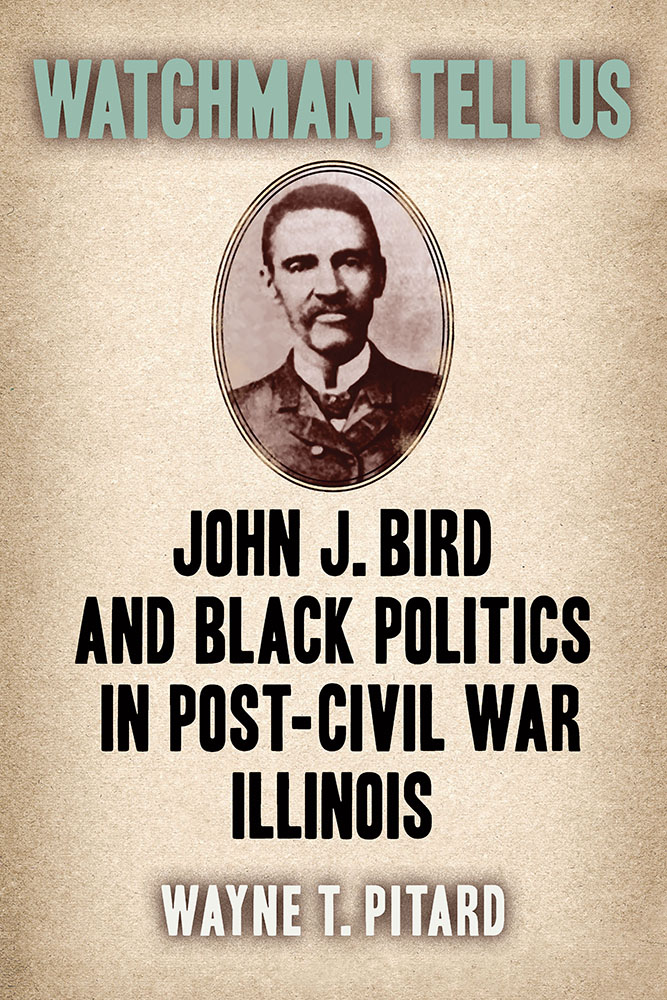

CARBONDALE, Ill. — John J. Bird was a well-known and highly respected leader in civil rights, politics and education more than 150 years ago in Illinois. A recently published book about Bird — who lived in both Cairo and Springfield — by Wayne T. Pitard looks to renew interest in a man who broke many racial barriers but whose statewide impact is overlooked.

Pitard will be honored Tuesday, Nov. 12, with the 2024 Friends of Morris Library Delta Award at Southern Illinois University Carbondale for “Watchman, Tell Us: John J. Bird and Black Politics in Post-Civil War Illinois.” The free, public presentation and award ceremony is at 5 p.m. in the library’s John C. Guyon Auditorium. A reception and book signing will follow at 6 p.m. in the first-floor rotunda. SIU Press published the book in September and will have copies available for purchase.

Pitard “has done a remarkable job in uncovering and chronicling” Bird’s story, said Judy Travelstead, Delta Award committee chair. “His achievements as the first in so many different fields are historic, and yet Bird is not known today. Pitard, in telling the story of Bird, also provides us with a history of Cairo from a different point of view, that of the Black community. This book is a must-read for anyone interested in the history of Illinois and particularly Southern Illinois.”

The award makes 121 Delta Awards given annually since 1976 by the Friends of Morris Library “to individuals who have contributed significantly to the preservation of the history and culture Southern Illinois region, either by their writing, or by other service.”

“Circuitous route” to learning of Bird’s story

Pitard, who lives in Champaign, said he’s “delighted and honored” for the selection.

“Having looked at the list of previous honorees, I find myself in very good company,” he said.

An emeritus professor of religion and director emeritus of the Spurlock Museum of World Cultures at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign (UIUC), Pitard said he became “fascinated” with Bird in 2015 when he came across a brief paragraph on Bird while doing research for a museum exhibit honoring the university’s sesquicentennial. Bird was appointed in 1873 by then-Gov. John Beveridge to the board of trustees of Illinois Industrial University, which later became UIUC, who were otherwise all-white. Pitard became curious and delved further into Bird’s background, and when historians “seemed unaware of him,” he began searching for 19th century information from resources, including newspaper clippings and city directories.

An emeritus professor of religion and director emeritus of the Spurlock Museum of World Cultures at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign (UIUC), Pitard said he became “fascinated” with Bird in 2015 when he came across a brief paragraph on Bird while doing research for a museum exhibit honoring the university’s sesquicentennial. Bird was appointed in 1873 by then-Gov. John Beveridge to the board of trustees of Illinois Industrial University, which later became UIUC, who were otherwise all-white. Pitard became curious and delved further into Bird’s background, and when historians “seemed unaware of him,” he began searching for 19th century information from resources, including newspaper clippings and city directories.

Pitard worked exclusively on the book for about 4½ years after retiring in 2016.

“What I discovered is that there was much more to John Bird than his board appointment and that, although now forgotten, he had been one of the most significant Black civil rights leaders and politicians in post-Civil War Illinois,” Pitard said. “I found him so remarkable that I couldn’t stop looking into his life until I wound up with a book-length manuscript.”

Bird was “dedicated to civil rights, a natural leader and organizer, an eloquent orator,” Pitard said. “He was admired as a man of integrity in both the Black and white communities, by his political allies and his enemies. He showed a remarkable facility for working with and gaining the confidence of people from a wide range of cultural backgrounds, both in the Black community and among whites.”

SIU Carbondale connection

Bird broke another racial barrier when he was invited to speak at the opening ceremonies of then-Southern Illinois Normal University in 1874, “the first time an African American had taken part in and addressed such a celebration,” Pitard said. Beveridge, along with the presidents of Northwestern University and Bloomington Normal School (now Illinois State) and Robert Allyn, the new SINU president, also spoke.

“Bird and Allyn came to be longtime colleagues. In 1889, Allyn wrote a letter to Gov. Joseph Fifer in support of Bird for a state position, in which he refers to Bird as ‘my friend,’” Pitard said. “This honorific occasion was tempered, however, by the fact that the local planning committee, which had made hotel and dining reservations for the other speakers, failed to do so for Bird, who had to walk 2 miles out of town to stay with a friend. This is an instance of the kinds of racist treatment that Bird, as a successful Black man, had to endure.”

Breaking racial barriers

Pitard said Bird, born in 1844 in Cincinnati, Ohio, to free parents “who educated him well and gave him a strong sense of duty” traveled to Cairo in 1864 “with the intention of aiding and organizing the large population of refugees from enslavement in the South who had settled there into a new, cohesive community,” Pitard said. “He immediately became the primary voice representing this community through the 1860s, ’70s and most of the ’80s. He fought tirelessly for their civil rights and was remarkably successful. He became a role model for activism in the late 19th century.”

Bird’s other accomplishments included:

- Being elected police magistrate in Cairo in 1873, becoming the first Black elected judge in Illinois.

- Leading the fight to create the first Black public school in Cairo.

- Becoming the most prominent Black Republican in Southern Illinois and a leader in the Black convention movement in Illinois from the 1870s through the 1890s.

- Becoming editor of three newspapers in the 1880s and 1890s, including The State Capital newspaper, which “played an important role in guiding political thought throughout the Midwest.”

“Bird’s entire career was influential across the state. In Cairo, he led the second largest Black community in Illinois to unparalleled political influence in the city, opening numerous opportunities of its citizens to enjoy wider rights than communities elsewhere in Illinois,” Pitard said. “He became a heroic figure with his appointment to the university and his election as judge in 1873. He played an important role in increasing the influence of the Republican Party in heavily Democratic Southern Illinois. His work with the state and national Black conventions allowed him to influence the way Black communities understood and acted upon the most significant issues that they faced.”

Forgotten ‘until now’

Pitard “firmly believes” Bird belongs with the ranks of other major Illinois Black leaders of the 19th century civil rights struggles who are remembered.

“Those leaders were mostly based in Chicago, where their stories continued to be told,” Pitard said. “Very little is currently known about the civil rights activities south of Cook County, and I think it is important to see and understand that major work was being done in Southern and Central Illinois that deserves to be an important part of the public narrative about the extraordinary struggle for rights in this state.”

Pitard added he hopes that people will be “fascinated by Bird’s extraordinary life and achievements and that they will gain an interest in the post-Civil War civil rights movement in the North that brought about great advances, although it was largely crushed by the two major political parties by the end of the 19th century. However, forgotten leaders like Bird had a strong impact on the next generation of the Black community, many of whom took up the mantle of civil rights themselves and passed it on to the following generations.”