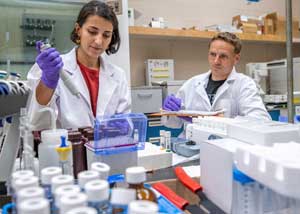

Doctoral student Alexander “Koaw” Zaczek works on one of three 600-gallon tanks holding largemouth bass at a research fishery south of Carbondale. SIU is working with partners using a $324,000 grant from the U.S. Department of Agriculture to improve intensive aquaculture methods for the fish. BELOW: SIU research assistant Asyeh Sohrabifar, left, and Zaczek,run tests on samples at a lab on the SIU campus as part of the largemouth bass study. (Photos by Russell Bailey)

August 08, 2024

$345K SIU study focuses on how to keep farmed largemouth bass from eating their own

CARBONDALE, Ill. – The largemouth bass is a popular sportfish among anglers, who know that familiar “thump.” But researchers at Southern Illinois University Carbondale are looking to find better ways to farm it to the table for humans by keeping the infamously cannibalistic species decidedly off its own menu.

Using a two-year, $324,000 grant from the U.S. Department of Agriculture, SIU researchers are working with Purdue University and local industry partner Big House Fish Farm on improving intensive aquaculture methods for largemouth bass and getting a more productive and predictable yield. The study will conclude this fall.

In addition to providing recreation, largemouth bass are also one of the most popular table fares, especially in live Asian markets. Largemouth bass have been farmed for nearly a century, although the target market typically is anglers fishing small lakes and impoundments for fishing.

In Southern Illinois, the market is growing, generating at least $3 million a year for local fish farmers with room for more, said Jim Garvey, director of the Center for Fisheries, Aquaculture and Aquatic Sciences at SIU and a co-leader of the study along with Habibollah Fakhraei, assistant professor of environmental engineering. The acceptance of largemouth bass as a food fish in live markets is relatively new, and raising them in high densities to maximize production in small ponds has presented challenges.

“Largemouth bass are top predators in lakes and are not really adapted to living at high densities,” Garvey said. “In the wild, they eat live prey and often eat each other. It’s not unusual for a pond containing a bunch of little bass to produce one or two surviving big bass that have eaten their brothers and sisters.”

The research, therefore, is aimed at determining ways to increase survival by reducing cannibalism in largemouth bass while encouraging them to eat formulated feeds.

A team effort

Along with Garvey, SIU researcher Hannah Holmquist, research assistant Asyeh Sohrabifar, post-doctoral student Giovanni Molinari, and doctoral student Alexander “Koaw” Zaczek are working on the project, which takes place in nine ponds near SIU’s Touch of Nature Environmental Education Center south of Carbondale.

Zaczek said the team is using three of the ponds to supply water to three 600-gallon tanks holding largemouth bass. Researchers also partitioned three other ponds to keep the fish separated, while three other ponds hold control group fish. The team is studying how the various holding methods impact the fishes’ survival and growth.

Fencing and netting prevent hungry local predators such as otter, great blue heron and great egret from enjoying the buffet, which totaled more than 11,000 fish at the project’s outset. Strict protocols govern the researcher team’s day-to-day interaction with the specimens and include feeding, cleaning, aeration, waste management, equipment maintenance and other factors, Zaczek said.

Close quarters being the order of the day, the team takes a particular interest in nitrogen cycles of each enclosure, watching for signs of trouble with the waste generated by the fish overwhelming the environment.

The team collects samples daily and weekly to run lab tests and monitor nutrient data and other factors, Zaczek said.

“We're looking to see, particularly in the split-ponds, if the ammonia that is generated by the fish waste is processed via the nitrogen cycle and more conducive to fish health compared to the control ponds,” he said. “Basically, the hope is that the ammonia released by the fish is broken down into nitrite and then nitrate in the non-fish-containing portion of the ponds so that the returned water to the fish of the pond contains minimal to no ammonia.”

Cutting down on cannibalism?

Encouraging fish to eat more evenly across the population might prove easier in denser populations, Zaczek said.

“We’re trying to get all the fish to take to the feed early,” he said. “In a big pond, where the fish are spread out, it becomes more difficult to ensure even feeding, and it’s harder to get fish to take to the feed early. The fish that do take to the feed early get a head start, grow big and are more likely to eat their cohorts.”

With the fish living in such conditions, cannibalism can certainly take a bite out of the bottom line. Discouraging this behavior in largemouth bass is a challenge, Zaczek said.

“Well, that’s something easier said than done,” he said. “The hope is the confined space and higher fish density will cause the fish to take to the feed better and eat more similarly, which also would encourage similar growth rates. They are less likely to eat each other if they are the same size.”

A growing market

With largemouth bass becoming a more popular culinary item, Zaczek said, the team’s research could help open important revenue paths for fish farmers. If either the tank-side or split-pond method prove to be more efficient, producers’ efforts might result in more fish surviving at more predictable sizes.

Success also might lead to other fish farmers experimenting with such methods on their own properties using other common species found in aquaculture such as catfishes.

“Buyers are happier if fish are of similar size, and sellers are happier when they are capable of delivering more product,” he said. “As in most industries, efficiency is always the goal in aquaculture.”

(Note to editors: Zazcek is pronounced “ZAY-check”; Asyeh Sohrabifar is pronounced “ah-SEE-yeh soh-RAH-bee-far”).