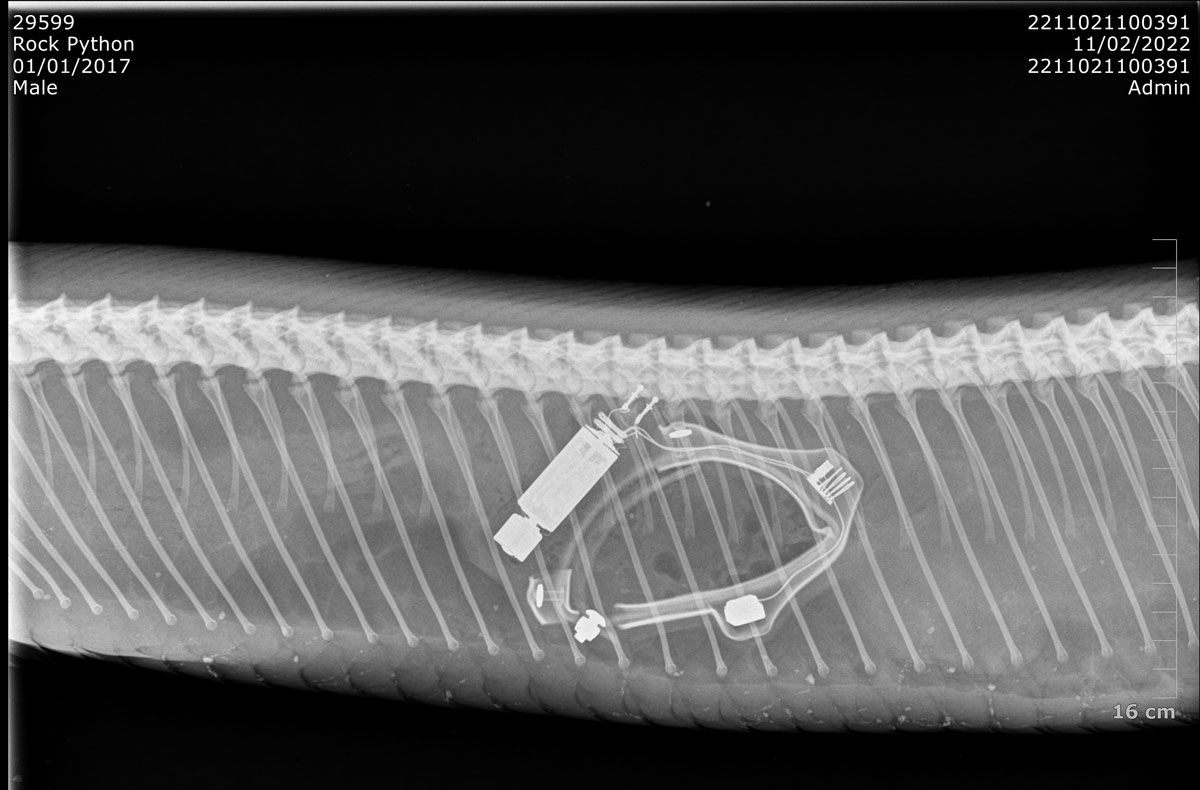

An x-ray image of a python taken by researchers in the Key Largo, Florida, area shows a GPS collar that had been fitted on a local opossum. Southern Illinois University graduate student Kelly Crandall said tracking python’s prey may help with detecting and removing the invasive snakes. (Photo provided)

January 26, 2023

SIU student’s research may lead to better control of invasive pythons

CARBONDALE, Ill. – When you’re a Southern Illinois University Carbondale student doing research far from home, sometimes discoveries happen in unexpected ways. Take the recent case of an opossum, a Burmese python and a GPS collar that may lead to better tracking and removal of the invasive species.

Since April, Kelly Crandall had been working on a U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service-funded study examining how human activities influence the movements of raccoons and opossums, as well as the impacts of environmental functions. The group is working around Key Largo, Florida, in and around Crocodile Lake National Wildlife Refuge.

A graduate student from Cassadaga, New York, with an interest in spatial technologies such as using GPS location data, Crandall was a good fit for the project. Having previously worked as a technician with the U.S. Geological Survey nearby, Crandall also brought a keen interest in the effects that invasive species, such as the Burmese python, were having on the mammal population, especially so-called mesopredators like raccoons and opossums.

“I specifically wanted to understand how supplemental food resources, such as feral cat feeding stations and unsecured garbage sources, might influence the movement and behavior of these animals,” Crandall said. “As native omnivores, raccoons and opossums play a role in the ecosystem which may include seed dispersal or population control of prey species. So, if raccoons and opossums are utilizing anthropogenic resources, I wanted to know how these ecological roles are being affected.”

An unexpected twist

Working with her adviser, Brent Pease, assistant professor in the forestry program at SIU, and collaborators at Crocodile Lake and The North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences, the project was going as planned. Crandall helped capture some 30 opossums and raccoons, fitting the critters with GPS collars.

But then on Sept. 8, some of the scientists on the project noticed the data coming back from the location collar on one of the opossums was indicating unusual movement.

But then on Sept. 8, some of the scientists on the project noticed the data coming back from the location collar on one of the opossums was indicating unusual movement.

Further investigation revealed signs of a bad end for the opossum and, following the signal from the collar, the scientists confirmed their hunch: Turns out the data had captured the opossum “moving” into the belly of an invasive, 12-foot-long Burmese python. Florida is home to an exploding population of the invasive snakes, as many pet owners release them into the wild when they become too large or a nuisance, and have now established breeding populations throughout south Florida.

Using the signal from the still-transmitting collar, wildlife officials were able to capture the 62-pound snake. In doing so, the team also confirmed a possible means of tracking and ultimately removing the elusive reptiles.

Is bad luck, good luck?

While not entirely surprised by the incident, Crandall said she learned a lot. Though one goal of the study was to detect pythons, there were still many unanswered questions.

“For instance, we did not know if a snake would be deterred by the collar and abandon the attempt to swallow the animal,” she said.

Apparently not. But in this case, the GPS collars also were equipped with a mortality beacon, which changes its signal after four hours of no movement from the collared animal.

“In this case, the collar recorded over 30 mortality events, but it continued to move around underground, which was very unusual,” Crandall said. “We theorized that a python might be responsible for these anomalies, but it was great to get confirmation of that theory when we were able to capture the snake.”

Pease said the team may have made an important bonus discovery.

“We think it’s important because these snakes have been very difficult to find, and this may prove to be an efficient tracking method,” Pease said.

Future plans

The python – the second-largest specimen ever captured in Key Largo – was euthanized using standard procedures. The necropsy revealed dozens of egg follicles that would have been viable, fertilized eggs – suggesting that this removal also prevented future pythons.

Scientists plan to continue evaluating how effective tracking python prey species is for detecting and taking out the invasive snakes.

“Removing this specimen by itself is hugely beneficial to the ecosystem, and now we have documented at least two male snakes on camera in the same area that the female was removed from,” Crandall said. “Now our goal is to find and remove those two males, and the whole incident shows that tracking prey species could be a feasible method of detecting and removing novel pythons from the ecosystem.”

Crandall will return to the area this summer to complete another season working in the field on the project. She hopes to complete her Master of Science degree in forestry in spring 2024 and pursue a career as a biologist working in wildlife management and conservation for a state or federal agency.

SIU has been key to pursuing her dreams.

“The forestry program at SIU emphasizes the importance of how habitat can influence species populations and behaviors. The environment here is welcoming and collaborative, and it has been a pleasure to meet other students and professors and hear what they have been working on. It is great to be able to learn so much from your peers,” she said.