SIU Professor of Zoology Gregory Whitledge stands at the university’s Center for Fisheries, Aquaculture, and Aquatic Sciences. Whitledge and others recently used the telltale chemistry contained in the growth rings of a bone from the ear of invasive Great Lakes grass carp to identify key breeding grounds for the fish. The information contained in the otoliths, or so-called “ear stones,” could help wildlife managers better target population control efforts aimed at the fish that crowds out native animals. (Photo by Yenitza Melgoza)

December 01, 2020

Grass carp’s ear bones reveal clues to controlling the invasive fish

CARBONDALE, Ill. – In fish, the fin bone is connected to the tail bone and so on. But for a researcher at Southern Illinois University Carbondale studying an aggressive invader, it’s all about the ear bone.

That tiny bone in the ear of the grass carp is exposing an important clue to controlling their numbers in the Great Lakes. The findings are contained in a paper by SIU Professor of Zoology Gregory Whitledge, recently published in Journal of Great Lakes Research.

Whitledge and others used the telltale chemistry contained in the growth rings from the bone to identify key breeding grounds for the fish. The information contained in the otoliths, or so-called “ear stones,” could help wildlife managers better target population control efforts aimed at a fish that crowds out native animals.

An ongoing issue

Multiple species of invasive Asian carp began threatening the ecosystem of America’s Great Lakes and river systems about a decade ago. Asian carp are present in the upper and lower portions of the Mississippi River, the lower Missouri River, the Illinois River and the Ohio River, for example. Several varieties – including the bighead and the silver, which can grow to 100 pounds and leap into the air – are present in Illinois waterways, as well.

Another of these species non-native to North America, grass carp, was introduced into the Great Lakes system some time ago. Working with a team of scientists, Whitledge found that grass carp are successfully reproducing in the rivers feeding Lake Erie. The study’s collaborators included other universities and U.S. Geological Survey, with Whitledge’s research funded by a grant from the Illinois Department of Natural Resources.

Defining the source of the problem

There was evidence of grass carp reproducing in two tributaries of Lake Erie in northwestern Ohio. However, no evidence of spawning has been found yet in several other tributaries to Lake Erie and the other Great Lakes, even though they are considered suitable for grass carp reproduction.

“One of our goals was to determine the extent to which the expanding population of grass carp in the Great Lakes is primarily supported by continued introductions from outside of the Great Lakes watershed versus natural reproduction by fish already present in the Great Lakes, as a result of prior introductions,” Whitledge said. “We also wanted to know whether otolith chemistry would show any evidence of grass carp reproducing in rivers other than the two in Ohio where eggs and larvae have been collected so far.”

Cooperative research

The team examined otoliths from grass carp captured by U.S. or Canadian federal, state or provincial natural resource agencies, which stay vigilant for their presence in various Great Lakes locations and tributaries. They also used fish caught by commercial and recreational fishers.

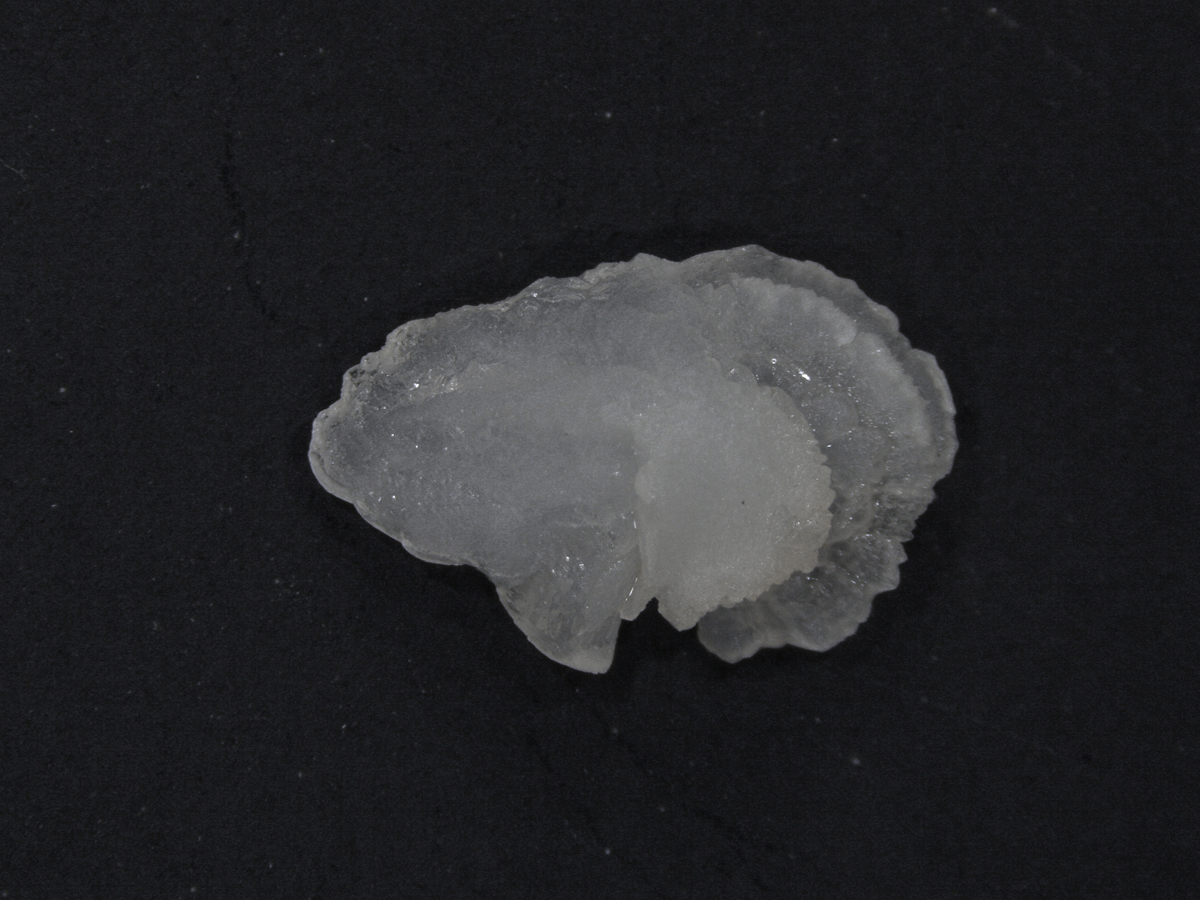

The bone, which aids the fish in hearing and balance, primarily is composed of calcium carbonate and grows throughout the fish’s lifetime, resulting in growth rings such as those found in a tree. That means it maintains important information about its environment and origin.

‘Ear stones’ reveal secrets

“For some chemical elements, the composition of the otolith reflects that of the water where the fish lives,” said Whitledge, who works at SIU’s Center for Fisheries, Aquaculture, and Aquatic Sciences in the School of Biological Sciences. “Otoliths are also inert after they’re formed, meaning the material that forms the stone is never altered or removed, so they contain a permanent, chronological record of the environmental chemistry experienced by a fish.”

Researchers analyzed the chemical composition of the otoliths, mainly looking at a stable oxygen isotope and the strontium-to-calcium ratios, which told the individual story for each fish.

“If there are differences in water chemistry among locations where a fish might have originated or lived for some time, we can use otolith chemistry to identify the source of an individual fish and potentially reconstruct its environmental history,” Whitledge said.

Scientists previously drew an important distinction between the two main sources of the invasive carp species – commercial aquaculture fish that either escaped or were released, and the wild-bred variety.

In this study, Whitledge used his expertise in this microchemistry technique and the scientific analytical instrumentation available at SIU to examine the stable oxygen isotope, which distinguished one from the other. Once he and the other researchers identified the wild-bred specimens, they further analyzed those using the strontium-to-calcium ratios, which acted like a fingerprint in identifying each wild fish’s river of origin.

Important findings could direct future efforts

The researchers’ findings will inform future efforts to control this destructive fish species. The study implies that controlling further expansion in the Great Lakes will require efforts to limit both natural reproduction and further introductions from outside of the Great Lakes watershed. It also should help focus control efforts on western Lake Erie tributaries, though checking additional potential tributaries for signs of grass carp is also warranted.

Lastly, Whitledge and the others identified some fish caught in Lake Michigan as having originated in Lake Erie.

“Controlling grass carp in Lake Erie is not just important for Lake Erie, but the other Great Lakes as well,” he said.

Invasive grass carp such as this one are found in the Great Lakes and their tributaries. SIU Professor of Zoology Gregory Whitledge and others recently used the telltale chemistry contained in the growth rings a bone from the ear of invasive Great Lakes grass carp to identify key breeding grounds for the fish. (Photo provided)