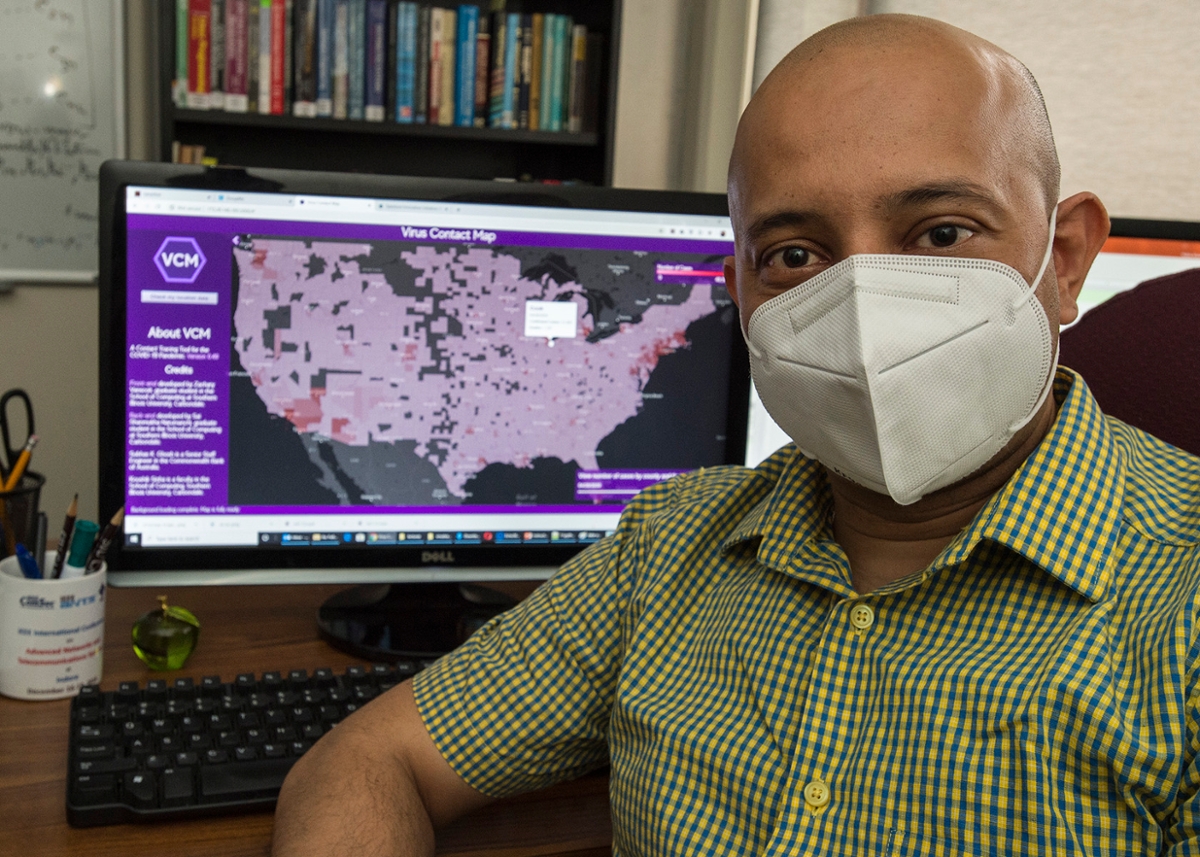

Koushik Sinha, assistant professor in the School of Computing at SIU, works on the Virus Contact Map, a new tool he and his team are developing to track COVID-19 and assist public health officials and the general public while protecting individual privacy. Once populated with the proper data and synced with common GPS information, the Virus Contact Map (VCM) would provide an important tool for avoiding exposure and tracking the virus’ spread. (Photo by Russell Bailey)

May 05, 2020

SIU researcher’s tool would improve tracking, avoidance of COVID-19 cases

CARBONDALE, Ill. -- In today’s information-heavy society, balancing the handy tools technology provides with the need for privacy is a constant concern. A health crisis such as the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic puts that tension in stark relief, as health authorities struggle with keeping the public informed while also protecting private health information.

A faculty member at Southern Illinois University Carbondale, however, believes he and his students have developed an application that will not only provide the public with the latest data on COVID-19 case locations locally, but also protect the identity of those diagnosed or exposed to the virus. Once populated with the proper data and synced with common GPS information, the Virus Contact Map (VCM) would provide an important tool for avoiding exposure and tracking the virus’ spread.

Koushik Sinha, assistant professor in the School of Computing, is working on an approach that uses Google timeline history to visualize whether individuals have come within dangerous proximity to the locations of known COVID-19 cases. The application, when fully operational, would give health officials and individuals the ability to see how the virus progresses over time locally and regionally. Health officials might further use it to identify areas as “hot spots” and issue warnings to the general public to avoid such areas, as well as designate them for decontamination.

An emerging crisis

Sinha and his team began working on the tool during spring break, just as the COVID-19 threat was becoming apparent. The idea emerged from Sinha’s ongoing research interest in crisis computing and “crowdsourcing,” wherein large numbers of people are enlisted to help solve a problem with resources or information. One of his previous projects, a tool called Artificial Intelligence for Disaster Response, used machine learning-based analytics of tweets and texts in real-time during humanitarian crises. AIDR has been extensively used by the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs.

The main information needed to bring the VCM online now is data from local health departments on COVID-19 cases.

“This is by far the most critical requirement as without it, the utility for general public will be greatly reduced,” Sinha said. “The tool will provide functionalities that we believe will be useful to both private individuals as well health officials.”

Potentially potent weapon

The system relies on smartphone GPS history gathered by Google when that option is enabled. Plans call to include other data sources such locations identified by WiFi access points.

The ability of the tool to use GPS data to identify hazards is well established. But importantly, the tool also would accomplish the sometimes more elusive goal of protecting individual privacy, despite relying partly on data gathered from private smartphone accounts.

No names or other identifying information will be associated with the location and diagnosis data it relies on, for instance, while other features and functions will protect data sources. Through an easy-to-use interface, users also will have the option to delete certain information – such as a home or work address – from the data set they provide in order to use the tool.

“There are multiple techniques that we will implement to ensure privacy,” Sinha said. “Our goal is to make the tool HIPAA-compliant.”

‘Seeing’ is believing

The tool will offer three ways to visualize or “see” the interaction between the virus’ spread and individual locations and movement. First, it will allow a user to see the number of COVID-19 cases, including fatalities, over time using a slidebar to control the time frame. Doing so might give a county health official the ability to visualize how the virus has progressed over time not only in their own counties, but in neighboring ones, as well, Sinha said Such information also might lead individuals to make safer shopping choices, for example.

“If I were to see my county has a considerable number of infections while neighboring counties do not, then I might feel safer doing my grocery shopping there rather than my home county,” he said.

The second visualization option would provide a color-coded map of all locations visited by individuals known to have COVID-19 during the last 48 hours. The visualization would use a function that combines both the number of COVID-19 cases to visit the location, but also how recently they did so before color-coding it.

As the virus is known to remain viable for a certain number of hours, such a map might again allow individuals to minimize their risk, Sinha said.

“For example, an individual might decide to avoid a store in a local county that has had a significant footfall of COVID-19 positive people in the recent past, and instead shop somewhere with a lighter footfall,” he said. “Another example could be, say in New York City, a person could use this information to determine if it would currently be safe to go for a walk or jog in Central Park as opposed to a Queens neighborhood.”

Health officials might also find this visualization helpful in designating local hot spots and issuing warnings.

Individuals can opt in

The third visualization would allow individual users to upload their Google timeline history data to the website, where an analytics engine would general a list of locations where they might have been exposed to a COVID-19 case in the recent past. The information would be presented again in a color-coded map with each visited location colored by the tool’s computed risk of exposure shown as high, moderate or low.

Although the VCM might warn of risk if needed, it also would prevent panic when risk is low.

“Providing a risk assessment of every contact and visited location would be a very useful feature to not only individuals who want to assess their chances of infection, but also to health officials in allocating resources for managing the COVID-19 crisis,” Sinha said. “As more users opt in and more data is available to the analytics engine for modeling risk, the accuracy of the risk assessment engine will improve.”

The user would then be able to hover the mouse pointer over each point to get additional information, such as the exact address of the location, when the contact happened and how long it lasted.

Combining certain visualizations for further analysis would give both health officials and the general public further insight into not only understanding the virus’ reach but also how to better minimize the risk of exposure on a personal level.

“For example, let’s say I first use a visualization that determines a certain grocery store is a safer place to go shopping on a certain day. Unfortunately, I unknowingly happen to come in close proximity with an asymptomatic COVID-19 person who later tests positive. Then this feature would allow me to determine if I was exposed to any such individual,” Sinha said. “The visualization of this map also allows users to control how far back in time and what sort of proximity distance would she like to use for generating the contact tracing map.

Privacy is paramount

Using GPS information in this way opens many questions on privacy, as well. Sinha said his team kept privacy – especially medical information privacy required by law – in the forefront of their minds when designing the tool.

For starters, the tool’s database requires only two pieces of information about individuals infected with COVID-19: their GPS location history and the time at which the individual tested positive. No other identifying information is needed.

Second, all location data is stored and displayed completely anonymously, thereby making it difficult to tie one hot spot location to a specific patient. Also, in cases where an individual chooses to upload his or her Google timeline history to assess risk of exposure, the system only requires the last 48 hours of data, which is stored only temporarily.

“We delete the uploaded file immediately after the results are displayed in order to maintain privacy of the users,” Sinha said.

Other restrictions also are built into the system, and the team also is developing a new type of encryption that will allow patients to maintain complete control over their data, while the tool’s analytic engine does the computations directly on the encrypted data.

“Addressing privacy concerns has been at the core of our innovation,” Sinha said. “So we have taken a very different approach than that being taken by most of the proposed contact tracing apps being developed around the world, some of which have already begun to raise a lot of concerns about privacy.”

Joining the fight

Sinha said he hopes to gain support and feedback from health officials on what features they would find useful on the tool and how it might be improved or modified. His ultimate goal is to develop a “mobile-friendly” version of the VCM tool that will serve the needs of both health officials and general public.

“We need support from the general public in contributing their data to this tool for the greater good,” he said. “As more people use it, the better will become our ability to provide accurate contact tracing and risk assessment results.”