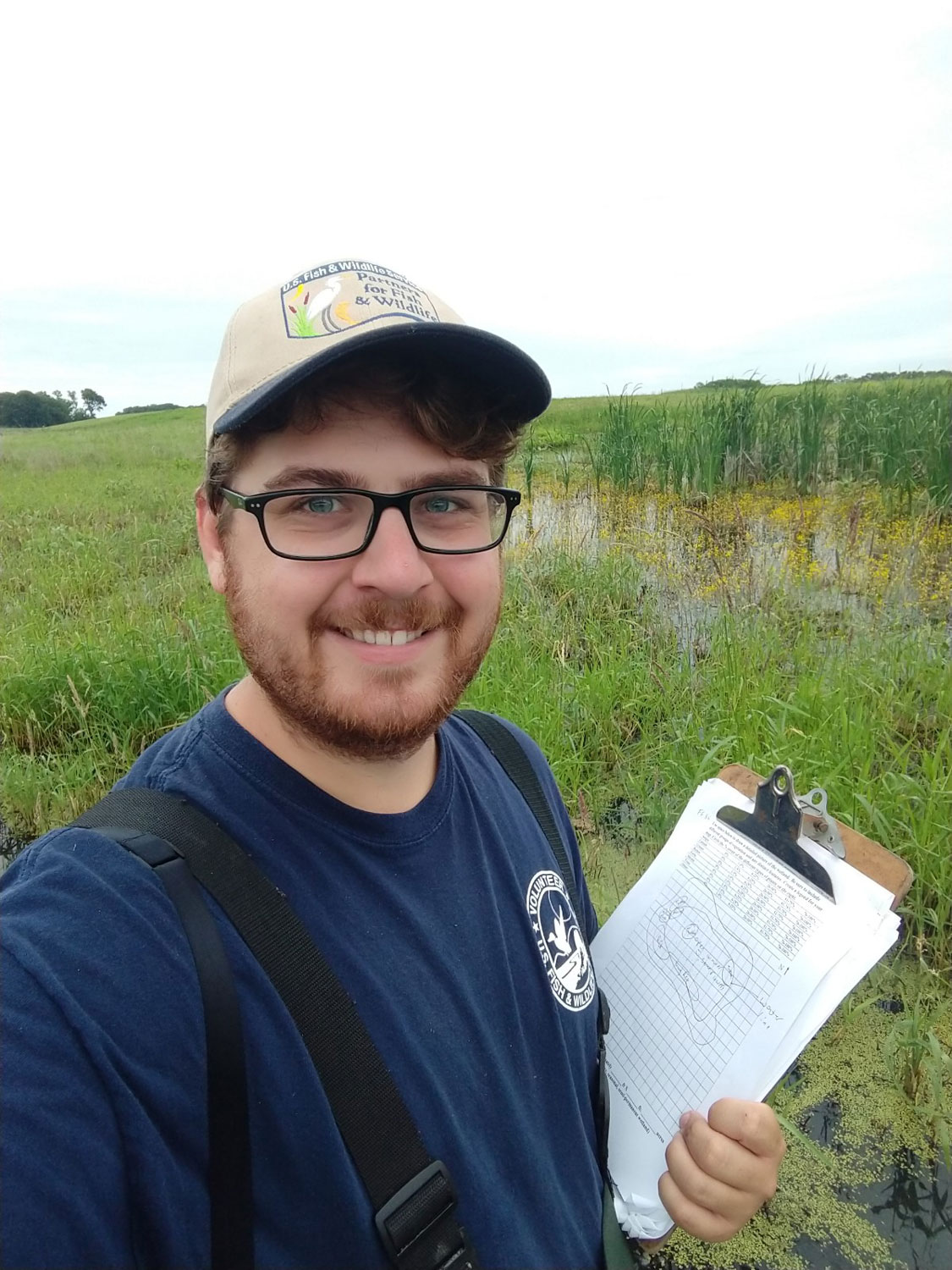

Mark Daniels, a graduate student at Southern Illinois University Carbondale, takes notes while surveying the Prairie Pothole Region in Minnesota. As part of his work toward a new graduate degree in wildlife administration and management at SIU, Daniels is spending his summer working to preserve the precious habitat the wetlands provide on his way to becoming a wildlife land manager. (Photo provided)

July 19, 2019

New graduate degree readies students for challenges of land, habitat management

The Prairie Pothole Region in the northern Great Plains is an immense, grassy land pocked by ancient glaciers that left thousands of shallow wetlands in their wake. As territories go, it’s a big one: comprising more than 275,000 square miles and stretching over five U.S. states and three Canadian provinces.

Somewhere in its midst, as it traverses Minnesota, Southern Illinois University Carbondale graduate student Mark Daniels is spending his summer working to preserve the precious habitat these wetlands provide. For Daniels, it’s foreshadowing what he hopes will be his future career as natural resource lands manger.

Daniels is among the first students to enter SIU’s pioneering professional science master’s degree in wildlife administration and management.

A program with a mission

A few years ago, agencies such as the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Illinois Department of Natural Resources and non-government organizations such as Ducks Unlimited Inc. began noticing that recent bachelors of science graduates in wildlife management weren’t adequately trained as land or people managers, said Michael Eichholz, associate professor the zoology degree program and director of the wildlife administration and management graduate program. Even graduate students earning master of science degrees typically received training focused only on research and population management, with the goal of creating wildlife population managers instead of those focused on habitat.

But that wildlife must live somewhere, and land management was being left out of the equation. In the new SIU program, students specialize in how to be natural resource lands managers, instead of focusing on the more general understanding of wildlife ecology without direction toward a specific position.

“Our program trains land managers, with the goal of addressing the shortcomings identified by the agencies that hire land managers,” Eichholz said. “Graduates are prepared for jobs such as refuge biologists or state wildlife and recreation area managers.”

A more specialized approach

As opposed to the more common master’s degree, professional science master’s programs train students for specific careers.

The centerpiece of the SIU program is a summer internship that emphasizes positions offering valuable field and other practical experiences, in place of writing a research thesis. Students also take classes that emphasize management of wildlife, habitat and user conflict resolution.

The curriculum was developed in cooperation with a team of advisers representing the natural resource agencies that hire the graduates. That means all the students receive additional training in general ecology, communication, habitat management and sociology.

“These are the skills they need to manage public and private lands dedicated to support of recreational use and wildlife populations,” Eichholz said.

Daniels said such programs are increasingly popular in natural resources disciplines, and for good reason.

“Considering I would likely already need to be working as a seasonal field technician to become a relevant candidate for a future job, the program was more valuable than what a thesis program could provide me,” he said.

So far three students have completed the SIU program, with three more, including Daniels, currently pursuing their degree. Four more students will begin the program in August.

Working in the ‘Land of 10,000 Lakes’

Some 10,000 years ago, melting ice sheets left thousands of depressions or “kettles” in the Minnesota plains. Each spring they fill in with water from melting snow, creating temporary wetlands that have a major impact on wildlife in the area. The area is one of the most important in North America for migratory waterfowl.

Over time, more than half of these features have been filled in and otherwise converted to agricultural uses. Such pressures between humans and wildlife is one of the obstacles future natural resource land managers such as Daniels may face.

Knowing he wanted to work on the management side of wildlife biology, Daniels said he took more classes that prepared him to plan and carry out management actions, as well as map and manage large sets of data. The program also is preparing him to work with stakeholders, landowners and others who may be impacted by such management plans.

“Basically, I'm trying to flesh out my curriculum to give me at least a little background on all aspects of wildlife management so that any transition to the variety of career paths can take place as seamlessly as possible,” he said. “This program in particular is quite flexible and allows the students to tailor their classes to suit whatever conservation or ecological career they envision themselves taking.”

Humans vs. wildlife, and finding the way forward

His internship has already introduced Daniels to the dance that sometimes exists between protecting human interests and the need to protect important wildlife and important habitat.

His work has seen him meeting with landowners and private lands biologists to discuss cooperating on easement programs to that end, resulting in high quality habitat. As part of that process, Daniels is responsible for checking up on the temporary wetland sites enrolled in the program, to ensure the habitat is in good shape.

Along the way, Daniels tries to educate and inform, battling misconceptions and resolving conflicts.

“Landowners often have the misconception that their land will be forced into public hunting availability or that over time the government can simply take their land,” Daniels said. “This is inaccurate, and while the government does sometimes purchase land for conservation purposes, all of those conditions are voluntary agreements from landowners. Aside from that, agreements are typically fairly straight forward.”

Flexibility is key

The Ornate Box Turtle is a well-known inhabitant of Southern Illinois and many Midwestern states. But in Illinois it’s listed as a threatened species, and several other states also are concerned about its fate and list it as a protected species.

That’s where Melissa Fry comes in. Working through the same program as Daniels, Fry is spending the summer working with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in the Upper Mississippi River National Wildlife and Fish Refuge on an effort aimed at continuing a conservation program for the well-known Terrapene.

“This program covers the whole range of wildlife, and I’m able to take a variety of classes,” said Fry, who hopes to pursue a career as a wildlife biologist for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service after graduation. “I wanted to learn everything because I didn't know what I wanted to do besides protecting and conserving wildlife, and other grad programs seemed too focused on one species or aspect of conservation.”