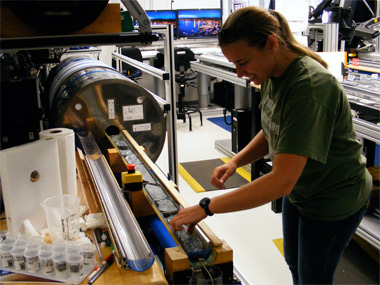

The core of the matter -- Sarah Friedman, a geology graduate student at Southern Illinois University Carbondale, analyzes core samples while aboard the research ship JOIDES Resolution off the coast of Panama in the Pacific Ocean as part of the International Ocean Discovery Program. Friedman, of Grayslake, served as the team’s paleomagnetist, tasked with analyzing magnetic properties of rock samples. Preliminary results of the work were published online by the scientific journal “Nature.” (Photo provided)

February 19, 2014

Student researches secrets of Earth’s crust

CARBONDALE, Ill. -- A geology graduate student at Southern Illinois University Carbondale recently went to sea with a group of researchers to peer through an unusual “window” in an effort to reveal secrets of the Earth’s crust.

Sarah Friedman, of Grayslake, spent nine weeks aboard the JOIDES Resolution off the coast of Panama in the Pacific Ocean as part of the International Ocean Discovery Program. She served as the team’s paleomagnetist, tasked with analyzing magnetic properties of rock samples.

Friedman said preliminary results of the work, published online by the scientific journal “Nature,” was an important opportunity for her as young scientist. It can be viewed here.

“This experience also showed me that I am able to work with people other than those I already work with,” Friedman said. “I was able to make contacts with new and established scientists and those contacts will be invaluable for the rest of my career.”

The scientists were hoping to exploit a “tectonic window” where the deeper part of the Earth’s crust has been bypassed, thereby providing a rare glimpse into the geologic processes that take place at greater depths. The area is known as Hess Deep Plutonic Crust.

For Friedman, looking beneath the waves is a natural way to find answers about the solid ground.

“The Earth’s oceans cover three quarters of our planet, so ocean crust makes up three quarters of the Earth’s rocks,” Friedman said. “Like most problems with ocean science it’s hard to get to your study area. The International Ocean Discovery Program supports geoscientists who study these rocks by providing access by means of an ocean drilling vessel.”

The international group of researchers’ primary approach was to take core samples from the area, drilling down and extracting rocks and analyzing their features. Friedman spent most of her time working in the ship’s laboratory.

“On the ship everyone works every day, and for this expedition that included working Christmas and New Year’s day,” Friedman said. “Everyone worked on a rotating 12-hour shift, so there were always people in the lab working.”

Friedman’s job included running magnetic equipment, cataloging data, interpreting data and creating figures and data reports to communicate findings to the team. With several different specialties doing their own work, communication was key, Friedman said.

“It helped with the flow of the core from one station to another,” she said.

The many samples they took confirmed the rock types that were predicted but not previously recovered and studied.

“Sometimes ocean rocks get uplifted onto continents,” she said. “This is rare, and geologists call these outcrops ‘ophiolites.’ There is an ophiolite in Oman that scientists believe to be similar to the Hess Deep tectonic setting, that is a fast-spreading, up to 13 cm a year of new crust created and a divergent boundary.”

Because the Oman ophiolite is on land, it is easy to study, Friedman said, and scientists can use it to infer many assumptions about ocean crust as it exists in nature, or “in-situ.”

But inference isn’t proof. For instance, ophiolites are rare, and may not be representative of ocean crust, thus our assumptions may be misleading about in-situ ocean floor, Friedman said.

That’s where the actual drilling comes into play.

“During the Hess Deep drilling we encountered a series of layered gabbros, which are rocks with a specific composition and colored banding, of which had never been found in-situ of the ocean floor. These rocks had been found and described in the Oman ophiolite.

“This finding helped us to piece together these two localities and realize that they may have more in common than originally thought,” she said.

Eric C. Ferré, professor of geology and Friedman’s graduate adviser, said she was assisting with work that is groundbreaking and important to understanding the Earth we live on.

“The main goal of the expedition was to sample lower crustal gabbroic rocks that formed at the fast-spreading East Pacific Rise, one of the planet's largest ocean ridges.”

Friedman said she is grateful for the opportunity to participate in important research while a graduate student at SIU.

“For me the best part of this experience was working with a group of scientists from different backgrounds, both academically and culturally, on the same project,” she said. “Everyone discovered a little piece of a puzzle and when everything was put together we ended up with a very interesting story.”