Drilling at sea -- The JOIDES Resolution, a highly specialized drilling ship, is presently home to Eric Ferré, professor of geology at Southern Illinois University Carbondale. Ferré is among the elite group of scientists aboard the ship who at this moment who are attempting to bring to the surface the deepest rock samples ever extracted from far beneath the seafloor. The group’s work could answer many questions about how the Earth’s oceanic crust forms and how the planet handles the heat associated with this massive process. The ship is dynamically stabilized and is one of just two of its kind in the world. Download Photo Here

May 13, 2011

Geologist part of elite team exploring Earth's crust

CARBONDALE, Ill. -- The Earth's crust is always changing, though rarely in ways that are visible to the naked eye. The changes come from many forces, not the least of which involves plate tectonics and the formation of new crust beneath the ocean from magma as it moves up from the planet's deeper mantle layer.

The best places to study this action -- areas where the crust is thinnest and the mantle not as deeply buried – are in the Pacific Ocean. One such place off the coast of Panama is home to an area where new oceanic crust is forming at the comparatively “super fast” pace of about 20 centimeters per year.

It’s in that area that a structural geologist from Southern Illinois University Carbondale is working among an elite group of Earth scientists aboard a highly specialized research ship. The team is attempting to bring to the surface the deepest rock samples ever extracted from beneath the seafloor, which could answer many questions about how the Earth’s oceanic crust forms and how the planet handles the heat associated with this massive process.

Eric C. Ferré, professor of geology in the College of Science, is aboard the drilling ship JOIDES Resolution. He is one of about 30 scientists on the expedition organized by the Integrated Ocean Drilling Program, an international research program seeking scientific understanding of the Earth through drilling, coring, and monitoring the sub seafloor.

The project’s goal is to drill and recover rock cores that come from more than 1,500 meters below the ocean floor in an area known for its fast-forming new crust. To do so, the team is deepening a hole drilled by a previous expedition as it seeks to understand how the crust and mantle interact. The project is another step in the overall goal -- begun half a century ago -- of ultimately drilling into the mantle itself.

The team brought its first core sample aboard last week after spending weeks re-establishing and stabilizing the previous drill site. Ferré’s role is examining a type of rock known as “gabbro,” which come from 1,500 meters below the seafloor.

The gabbros can tell scientists a lot about how that specific layer of Earth -- the oceanic crust -- cools over time. It’s an important question, as that particular type of crust covers about 75 percent of the planet’s surface, and how it deals with heat is crucial to understanding other systems, such as climate.

“The heat budget of the planet is crucial to understanding if climate is driven internally or by external forces,” said Ferré, who is communicating with colleagues on land via satellite-based email while onboard the ship. “For example, the mechanisms of heat transfer are yet unknown in the oceanic crust, which means that we do not know if oceanic water does contribute significantly to cooling the rocks from the lower crust or not.”

Ferré’s team is trying advance the understanding of how the Earth’s crust is formed in such mid-ocean ridges. The area they are working in is home to 15-million-year-old ocean crust that dates back to a period of “super-fast” crust formation that allowed the new crust to form a ridge as it piled up faster than the seafloor spread.

Ultimately, the research project also will help scientists understand how the Earth gets rid of heat in its oceans, he said.

“This layer of the oceanic crust has never been drilled in-situ before and therefore scientists on board have great expectations,” Ferré said. “We want to understand heat transfer processes in this very important layer of the lithosphere. This ultimately will provide useful information on how the Earth cools with time.”

The team hopes to deepen the existing 1,500-meter hole by at least another 400 meters, which will allow its members to recover gabbros from the lower levels of the Earth’s crust. Scientists expect this area of transition between the crust and mantle to yield many secrets on how the ever-changing Earth works, Ferré said.

In addition to looking for clues about heat transfer, Ferré also will focus on finding out whether the gabbros have a preferred orientation present in their mineral grains, which would tell him which direction the magma that formed them was moving when it formed the rocks some 15 million years ago.

“We do not have direct observations of (gabbros’) structure,” Ferre said. “We need to measure their preferred orientation in order to understand how the lower oceanic crust is formed and ultimately to understand at a large scale how plate tectonics actually works.”

The work has its roots in a 1961 research effort to drill through the Earth’s crust and into the mantle. While it failed, scientists remain keen on learning more about the mantle, which can hold the answers to many questions about the planet’s history and composition.

Ferré’s work with the international group aboard the 470-foot scientific research ship should take about six weeks. To follow their progress, visit the following websites.

http://ferreiodp335.blogspot.com/

http://iodp.tamu.edu/scienceops/expeditions/superfast_rate_crust.html

http://iodp.tamu.edu/scienceops/sitesumm.html

Doing his job -- Eric C. Ferré, professor of geology at Southern Illnois

University Carbondale, examines a rock core aboard the drilling ship JOIDES

Resolution. Ferré is one of about 30 scientists on the expedition organized by

the Integrated Ocean Drilling Program. After examining and describing all

samples macroscopically in detail, Ferré helps select the best 10 pieces of the

day for further analysis. The group's work could answer many questions about

how the Earth's oceanic crust forms and how the planet handles heat associated

with this massive process. Download Photo Here

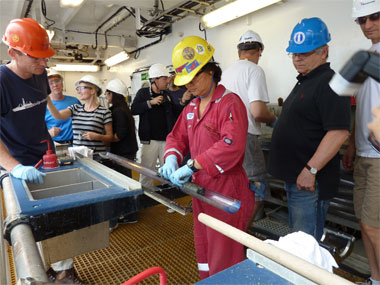

Drilling for science -- A team of drillers works on the drill floor of the

JOIDES Resolution, which is temporarily home to Eric C. Ferré, professor of

geology at Southern Illinois University Carbondale. Ferré is one of about 30

scientists on the expedition organized by the Integrated Ocean Drilling Program.

Drilling into hard rocks deep beneath the seafloor requires exceptional professional

espertise. The group's work could answer many questions about how the Earth's

oceanic crust forms and how the planet handles heat associated with this

massive process. Download Photo Here

Core on board -- Following its 5,000-meter ascent from beneath the seafloor

and to the ocean's surface, researchers examine rock cores as they arrive onboard

the JOIDES Resolution. Among them is Eric Ferré, professor of geology at

Southern Illinois University Carbondale. Ferré is one of about 30 scientists on

the expedition organized by the Integrated Ocean Drilling Program. The group's

work could answer many questions about how the Earth's oceanic crust forms

and how the planet handles heat associated with this massive process.

(Photos by Benoit Ildefonse) Download Photo Here