Danger sign -- A tiger walks along a road near a tiger reserve in central India. Clay Nielsen, an assistant professor with the Cooperative Wildlife Research Laboratory and the Department of Forestry, is working with people to keep them safe from the tigers that live on the reserve, near many farming villages. (Photo provided) Download Photo Here

April 11, 2011

Wildlife expert seeks clues to tiger attacks in India

CARBONDALE, Ill. -- Humans all over the world live in proximity to one danger or another. But a Southern Illinois University Carbondale researcher is working with people in India to keep them safe from a particular variety of next-door danger that weighs 400 pounds, walks on four legs and is a hunter and stalker by nature.

Clay Nielsen, an assistant professor with the Cooperative Wildlife Research Laboratory and the Department of Forestry, is assisting wildlife managers in central India as they look for ways to protect local villagers from tiger attacks. In the last five years alone, tigers have attacked members of the rural population 70 times, with 65 of those attacks being fatal.

The point of conflict centers on the interface between the estimated 79,000 people populating small villages around edges of the approximately 435-square-mile Tadoba Andhari tiger reserve, which is home to 35 to 40 tigers. Tigers, like many animals, normally disperse as they search out their own territory, and Nielsen hypothesizes many of the attacks stem from this naturally occurring behavior.

“Of course, as many wildlife do, they don’t always stay within the reserve. It’s an unfenced area. So animals disperse naturally from the reserve,” Nielsen said. “And that’s a big concern. When tigers leave the reserve, they’re in a rural landscape where there are lots of people, mostly farmers.”

Nielsen’s past efforts include work on dispersing cougars in the United States and jaguars in Mexico. He’s also worked on reducing human-animal conflicts in other areas where civilization and the wild exist in close proximity.

With this track record, a non-governmental organization in India called the Tiger Research and Conservation Trust (TRACT) contacted Nielsen during the summer and invited him to collaborate on its effort to cut down on the often-fatal interaction between the big cats and local villagers living around the reserve.

TRACT’s main method of reducing such attacks now consists of conducting patrols around the reserve’s perimeter, looking for signs of a wayward tiger. If they spot such signs, they warn local villagers to be extra vigilant.

Its members also have collected data about the 70 attacks, recording parameters such as location, time of day, type of victim and topography.

Nielsen hopes to use the data to identify similar characteristics inherent in the attacks in an attempt to predict where and when they are most likely to occur.

Also, a large proportion of the victims have been female, who are typically smaller in stature than males, Nielsen said. A large proportion also were attacked while sitting or squatting, which might fool the tigers into thinking the victim was a common local species of monkey that often assumes the same pose.

“Tigers look at humans as prey; they’re killing them as a prey species,” he said. “They might be confusing them with other wildlife in the area that they’re used to eating.”

The sheer number of attacks is concerning as well, Nielsen said.

“It is a high number of attacks. And what’s unique is that there haven’t been a lot of research efforts of tigers in this type of landscape that is so dominated by people,” he said. “A lot of studies that are done have been in the more pristine areas. But this is the interface between people and tigers that exists a lot in India and certain parts of China. This area is loaded with people, yet in the middle of it we have this pristine tiger reserve. As a researcher, that interested me.”

So much so, that Nielsen -- looking for a “cool” place to visit over winter break, anyway -- paid his own way to India for a nearly two-week visit, spending about a week of it with TRACT members and seeing the area in question up close.

The group spent a great deal of time hiking and driving around the reserve, looking for signs of tigers and leopards, another concerning species, though less troublesome than the tigers. They found tracks for both species and observed the landscape both within and outside the reserve, noting the stark difference between the two.

The reserve is home to the ideal tiger environment, with a thick growth of bamboo plants down low and teak trees towering overhead. It’s thick, dark and great for a silent, deadly predator that stalks its prey and pounces.

Just outside the reserve, however, it’s a much different story. Villages, rice fields, degraded forest and grazing livestock dominate the landscape. A tiger, used to the dark, lush forest, is out of place there and Nielsen believes humans kill many such animals as they disperse from the reserve.

“You think of a tiger getting out there, after leaving the jungle where there’s lots of prey, lots of cover. Outside, there’s not nearly as much prey, because the villagers are using that prey in some cases. There’s also not as much cover. But there are a lot of other prey sources (villagers) out there working in the fields,” Nielsen said.

Globally, there are probably fewer than 5,000 tigers living in the wild, Nielsen said, with only about 1,500 throughout India. So getting the lay of the land in and around the reserve was important to understanding the challenges of keeping both humans and tigers safe.

“There’s not a whole lot of places for the tigers to live other than the reserve,” he said. “Even in the reserve itself, they are threatened by poachers who are collecting tigers for their body parts for use in traditional medicines.

“But if we’re going to reduce human-tiger conflict we have to work with the people who live with the tigers. It’s the villagers who are threatened, who are scared and who are having their livelihoods or their lives threatened by the tigers. We’re hoping this research can really focus on educating local folks on how to minimize fatalities or injury from tiger attacks,” he said.

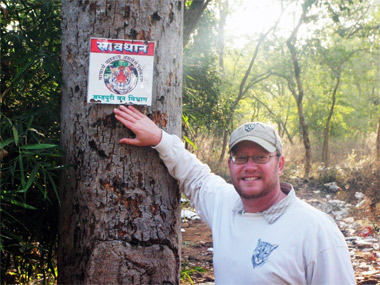

Warning to residents -- Clay Nielsen, an assistant professor with

the Cooperative Wildlife Research Laboratory and the Department of

Forestry, stands next to a sign warning area residents of possible tiger

lurking in the area in India. (Photo provided) Download Photo Here

Edge of safety -- The edge of a tiger reserve in central India is

shown in this picture. (Photo provided) Download Photo Here