January 05, 2011

Sociology professor’s new book earns honor

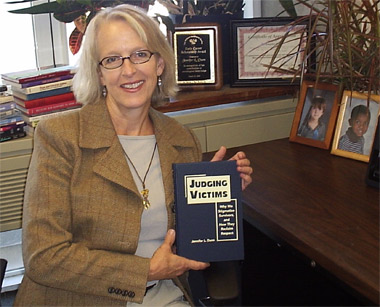

CARBONDALE, Ill. -- Jennifer Dunn, associate professor of sociology at Southern Illinois University Carbondale, started out the new year by landing on the 2010 Outstanding Academic Title list presented by Choice magazine.

Her book, “Judging Victims: Why We Stigmatize Survivors, and How They Reclaim Our Respect,” is available from Lynne Rienner Publishers. Irving E. Rockwood, editor and publisher of Choice magazine, said the academic books on the Choice list are selected from more than 7,000 titles reviewed over the course of the year, and represent less than 3 percent of the more than 25,000 titles submitted to Choice during the year.

“These outstanding works have been selected for their excellence in scholarship and presentation, the significance of their contribution to the field, and their value as important -- often the first -- treatment of their subject.”

K. Baird-Olson, serving as Choice magazine reviewer, said Dunn’s book is “essential” and a “must-read for policy makers and criminal justice and social service personnel.”

In her book, Dunn argues that some of our beliefs lead us, as a society, to feel sympathy only for certain types of victims, while we tend to blame others for their own misfortunes.

“We have really deep-rooted ideas about agency -- free will, self-efficacy. We blame victims because we deeply believe everyone has choices, no matter what,” Dunn said during a recent interview about her book.

Dunn’s book examines the narratives of four types of victims -- namely, victims of rape, domestic violence, incest and clergy abuse. Dunn notes how the vocabulary of these narratives demonstrates the shifting perceptions of victims -- as blameworthy, blameless, heroic or pathetic -- and how these shifts influence our society’s level of sympathy to them, and, in turn, the victims’ legal and social standing.

“Images of victims must be consistent with what we think we know about the world and how it works, with what we believe is right or wrong, just or unjust,” Dunn writes, noting further that “successful creation of sympathetic victims is complicated.”

To understand the argument, think of a courtroom and a trial of someone accused of committing date rape. The defense attorney’s argument will almost certainly be that the sex act was consensual or that the defendant had reason to believe it was consensual -- that the victim is not a victim. The prosecutor will, of course, argue that the victim did not or was not able to consent in the attempt to create a sympathetic victim. The public will be divided -- some will say the defendant took advantage of his victim and committed a crime, while others will insist the victim implied consent by her behavior. The arguments, both in the court and in the public, focus on our perceptions about what makes a victim a victim. Our perception of a victim is informed, in part, by our ideas about choice -- did the victim make so poor a choice in what she wore or in where she went or in how she behaved that she cannot be considered a victim?

Dunn notes that the narratives of rape victims address the issue of choice almost without fail. Victims will say they were threatened, they were afraid, they were forced -- the narratives never seem to take for granted that the victim is a victim.

Narratives from victims of domestic violence are similar, Dunn noted. The victims address, even without prompting, questions of choice -- why they didn’t leave, why they returned, why they tolerated abusive behavior. Our perception of whether they are victims and deserving of sympathy or compassion depends on whether we believe they had a choice. Because we do, as a society, believe so passionately in choices and decision-making, narratives from victims of domestic violence tend to explain the victims’ behaviors almost as if they are the ones to blame for what has happened to them, even if what has happened is particularly violent or cruel.

“Victims feel they have to explain why they didn’t choose not to be a victim,” she said, explaining what she calls the Cultural Code of Agency. “We believe people have agency -- we don’t believe a person is a victim unless they can show they had no choice. At the same time, we devalue the qualities a person must have to meet this cultural code of being a victim. Even the victims follow this code -- they blame themselves.”

This, Dunn argues, is nothing less than judging victims.

“It’s a cultural dilemma, these ‘rules of victimization,’” she said. “A person becomes a ‘deviant’ either way. If you don’t meet the cultural expectations of a victim, then we blame you. If you do, then we judge you for your helplessness.”

Activists in the social movements that have brought these victims as a group into the public consciousness have responded by attempting to establish “the necessary and fundamental claim of innocence” for the victim group. The narratives, Dunn notes, highlight impediments to choice besides just physical force -- a domestic violence victim, for example, may be bound by sociological and psychological constraints as powerful -- or even more so -- as physical restraints.

Activists in these “survivor movements” address some of these less tangible factors that rob a victim of choice, Dunn notes in her book, citing the emergence of rape crisis centers, battered women shelters, therapists specializing in the long-term consequences of childhood sexual abuse and changes in religious institutions as examples.

However, she notes, the issue is far from settled.

“We blame victims if they are not helpless, but sometimes we do not respect helpless people very much or identify with them,” Dunn writes. “… If we start to think of victims as ‘survivors,’ will we still see them as needing our help?”

Dunn’s first book is also an award-winner. “Courting Disaster: Intimate Stalking, Culture and Criminal Justice,” a book she completed during her third year at SIUC, earned the Charles Horton Cooley book prize. In addition, her scholarship appears in many prominent journals, such as “Social Problems,” “Sociological Inquiry,” “Deviant Behavior,” and “Violence Against Women.” In 2008, the Midwest Sociological Society recognized her accomplishments with the inaugural Early Career Scholarship Award.