Cultured -- In her lab, graduate student Laurie J. George inspects her stock of hibiscus cuttings that supply the nodes, or plant starts, she uses in her research. (Photos by Jeff Garner) Download Photo Here

December 01, 2010

‘Cookie’ may help reduce costs for plant growers

(Editor’s Note: Kathryn Jaehnig, a member of our staff since 1988, passed away suddenly on Saturday, Nov. 27, 2010, at the age of 61. She was a caring individual and dedicated professional, and we will miss her -- along with her many talents and her contributions to the University. A memorial service for Kathryn is set for 4 p.m. on Friday, Dec. 3, at the Unitarian Fellowship, 105 N. Parrish Lane, Carbondale. This is the last news release that she prepared. -- Tom Woolf)

CARBONDALE, Ill. -- Plant propagators have been using manmade “seeds” to produce new shrubs for several decades. Now, a researcher from Southern Illinois University Carbondale has developed a “cookie” that can yield five times as many plants as the artificial seeds do.

Made from a mixture of processed kelp, tissue culture media and calcium chloride, the cookie is chemically similar to natural seed coverings. By varying the concentrations in the mix and adjusting the amount of time spent sterilizing it, Laurie J. George, a doctoral student in the College of Agricultural Sciences, can increase the number of nodes, or plant starts, the mix can protect from a single start to five. After four weeks of refrigeration and three weeks under some lights, they’re ready to grow.

Why cookies? Think dough.

“The artificial seeds encapsulate individual nodes, which takes a lot of time and labor,” George said. “While there are machines that do encapsulation, they’re costly, and they have a lot of moving parts which require maintenance.

“What I am trying to do is reduce these costs by focusing on mass encapsulation. It’s a technique smaller operations could use without a high cash outlay, and it can increase the numbers of plants that might not produce viable seeds on their own, plants that are rare and plants where we need to preserve their germplasm.”

George has been working with a cultivar of Hibiscus moscheutos called ‘Lord Baltimore.’ This hardy perennial, sometimes called a swamp mallow because it likes bogs and marshes, can grow 5 to 6 feet tall each season and bears dramatic red flowers the size of a dinner plate.

Despite some early challenges -- everything from what George refers to as a “high learning curve” in tissue culture (the process by which she gets the stock plants that supply the nodes she needs) to power and refrigerator failures to thrips in the lab -- George has mastered the art of the cookie, at least as far as ‘Lord Baltimore’ is concerned.

“We have it pretty much down pat in getting plants started, and I am having really good luck in getting them established and growing them out,” she said.

“I’m focusing now on improving the survival rate after cold storage. Currently, between 70 and 75 percent survive, so the majority is re-growing and being reproduced as plants we can sell. But you want to have 100 percent survival rates.”

George also is attempting mass encapsulation with ‘Snow Queen,’ a cultivar of the native Hydrangea quercifolia, a shrub prized for its showy look and exfoliating bark. This is proving trickier.

“It’s been a learning process for the hydrangea because it’s a totally different process from the hibiscus,” George said. “The cookie matrix had to be different, the sterilization process had to be different.

“Hydrangeas also are slow growers in tissue culture. Instead of a month or month and a half to get plant material, I’m having to wait two to three months.

“I’m going to have to step back and readjust the tissue culture medium. I’m also going to have to resolve an exudation problem (where secondary compounds in the plant tissue emerge, and contaminate the growing media, killing the sprouting nodes).”

Because the cookie has a greater mass than a “seed,” contamination presents more of problem.

“I’m trying to get down to less than 10 percent,” George said.

In addition, she is trying to answer questions of a larger nature. Will mass encapsulation protect the nodes better than individual encapsulation does? Will it allow them to remain in cold storage for longer time periods — say, a year or longer? And will they re-grow as well or better than individual nodes once cold storage ends?

“I am hoping that because I have more material around the roots, I will have a better survival rate, but you never know,” she said.

Cookie maker -- Graduate student Laurie J. George

notes that the hibiscus nodes in a 'cookie' she

concocted of processed kelp, tissue culture media

and calcium chloride have sprouted.

Download Photo Here

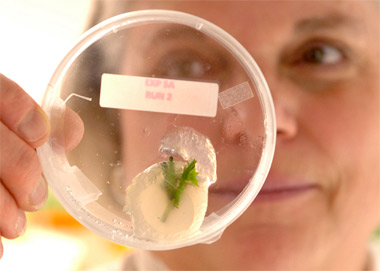

Roots, shoots, leaves -- With a Petri

dish acting as a mini-greenhouse, a

hibiscus 'cookie' begins to grow.

Download Photo Here

Breaking out -- After spending time in

the 'cookie,' these hibiscus starts have

put down roots and are leafing out.

Download Photo Here