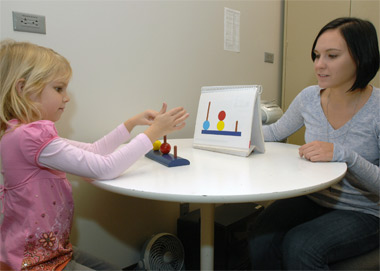

Testing cognitive ability -- Laci Trusty, research assistant, conducts non-medical tests to ascertain cognitive ability and executive function in children ages 8-12 as part of Michelle Kibby’s research of the co-morbidity, or co-existence, of both conditions in children. This part of the testing helps identify children with ADHD, dyslexia, both or neither. (Photo by Russell Bailey) Download Photo Here

November 30, 2010

Study seeks answers to ADHD-dyslexia in children

CARBONDALE, Ill. -- Southern Illinois families are an integral part of Michelle Kibby’s efforts to understand the link between ADHD and dyslexia.

Kibby, an associate professor of psychology at Southern Illinois University Carbondale who holds a cross-appointment in the SIU School of Medicine, investigates ADHD and dyslexia in children. In particular, she examines the comorbidity, or co-existence, of the two conditions. Earlier research found that about 20-40 percent of children with ADHD also show signs of dyslexia, and vice versa. That percentage is higher than would be expected by chance, Kibby said, and through her research she investigates the reasons why a child would have both conditions.

Ultimately, Kibby hopes her research will help children by contributing to earlier diagnosis of both conditions and a better understanding of what causes them, and what causes them to appear together in some children.

“A better understanding of why these two conditions present themselves together may lead to earlier interventions,” Kibby said. “And if we can learn what causes ADHD and dyslexia, we can better advise how these conditions should be treated.”

Kibby has a grant from the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, that funds part of her research. That grant, which began this month, continues for the next three years.

Kibby, still at the very beginning of this phase of her research, hopes to amass data on at least 100 children for her study. She said she relies on the greater Southern Illinois community from which to draw subjects for the study. She is looking for children ages 8 to 12 who have dyslexia, ADHD, both conditions, or are typically developing. The narrow age range applies because brain development occurs so rapidly.

Children in the study come to Kibby’s on-campus testing site for a full day of non-medical tests administered by graduate students who assist Kibby in her research. These tests measure various thinking skills such as executive functioning, reading, intelligence, attention, memory, language, and visual processing, along with motor skills such as fine motor, coordination, and visual-motor skills. In addition to the testing, children also complete an MRI scan, which she and her students will use to study the frontal lobe.

Kibby, who also is a child-clinical neuropsychologist, is qualified to diagnose ADHD and dyslexia. Children do not need a prior diagnosis of either dyslexia or ADHD to participate in the study, she said. Kibby is also looking for typically developing children as a comparison group.

Dyslexia, she noted, is not just a tendency to transpose letters. In clinical terms, it refers to a neurological condition that makes identification of written words difficult. Kibby stated that this inability to read words is likely due to a combination of factors including poor phonological processing, difficulty memorizing irregular words, and poor executive functioning, with each child only displaying some of these deficits. ADHD is also likely due to a separate combination of factors.

Kibby’s earlier research indicates that some sub-groups of children with ADHD and dyslexia have frontal brain lobes of atypical size. The frontal lobe governs executive functioning. Her lab tests help her analyze the children’s executive functioning in six areas: problem solving, planning, working memory, rapidly generating ideas, behavioral inhibition, and task shifting. For example, some of the tests measure a child’s ability to remember new facts or elements for the duration of a task, some measure how easily a child can shift from doing one task to another and back again, and others note a child’s level of impulsiveness.

The MRI scans contribute to a brain-tracing project that is part of the research. Kibby uses a software program to trace the brain images to measure frontal lobe size and form. A challenge there, she said, is ensuring consistency in measuring. The process is painstaking and time-consuming, but through it Kibby hopes to find some explanations for the presence of both ADHD and dyslexia in children.

“I’m looking at the possibility that poor executive functioning, stemming from differences in the frontal lobe, are at the root of the comorbididty,” Kibby said. “I don’t think my study will explain everything about what causes dyslexia and ADHD, but it should help to explain one potential cause of the disorders. The goal of future projects is to illuminate other shared and dissimilar causes of the two disorders, as each disorder likely has multiple causes that vary across individuals.”

Kibby’s grant-funded period began only very recently so answers are years in the future. In the meantime, as she pursues her own research, Kibby is able to help SIUC students by including them in her research. Her grant provides funding for graduate student and undergraduate assistants, and Kibby has been able to bring some undergraduate volunteers in on the research as well.

“It’s a unique experience for students to be involved with this level of research as undergraduates,” Kibby said. “Undergraduates are involved with multiple aspects of the lab, including the testing, data entry, recruitment of participants, and various data projects. Paid undergraduate assistants also help with the tracing for the frontal lobe project.”

The children who participate in this study receive T-shirts and MRI-generated brain images as souvenirs of their experience. Their parents get a detailed and comprehensive neuropsychological report of the child’s cognitive strengths and weaknesses, along with suggested strategies for parents to help their children get the most from their school experiences.

Parents and legal guardians interested in including their children in this research can contact Kibby at 618/453-3562 or by email at mkibby@siu.edu.