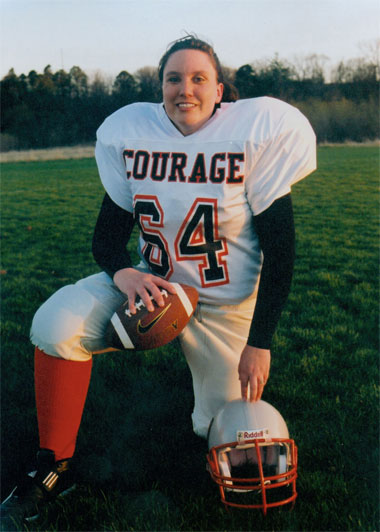

Suited for the game -- Clad in her pro-football uniform, former Des Moines Courage team member Bobbi Knapp, now an assistant professor of kinesiology at Southern Illinois University Carbondale, serves as proof that women want to and can play full-tackle ball. (Photo provided) Download Photo Here

February 05, 2010

Female pro football players out to win … respect

CARBONDALE, Ill. -- One female football team wins five national championships in six years, the other plays in bras and garters. Guess which one reporters cover.

There’s a reason for that choice, said Bobbi Knapp, assistant professor of kinesiology at Southern Illinois University Carbondale and former member of the Des Moines Courage (now the Des Moines Crush).

“Stereotyping female athletes as attractive and feminine shifts attention from their physical abilities to their looks,” Knapp observed.

“It lessens the symbolic threat sportswomen pose to what some in the sociology of sport refer to as ‘one of the last bastions of masculinity.’”

Media Advisory

Reporters may call Bobbi Knapp at 319/321-6505.

Organized football for women took off in the 1970s. It now includes more than 125 teams, but you’d never know it from the sports pages.

“If you see media coverage at all, it’s usually in features or local news, but more often there’s an overriding silence surrounding women’s participation in football, giving the public the impression that women’s football and consequently woman football players do not exist,” Knapp said.

“In women’s football coverage in the national media, there’s no noticeable increase in the level of coverage from 1970 to the present, even though the number of women playing football is substantially higher now.”

This matters, Knapp believes, because the media play such a powerful role in shaping how we see the world of sport. By ignoring woman football players altogether or focusing only on the pretty, shapely ones while emphasizing the “mannish” qualities of those who play full-contact ball, sportscasters and reporters reinforce society’s idea that football is a man’s game.

So what’s a woman who wants to kick, catch, pass, run and hit hard to do? Learn to define herself rather than letting others do it for her, said Knapp, whose doctoral dissertation focused on the women of the Detroit Demolition.

To find out what goes into the making of a female player and her team, Knapp spent two years attending Demolition practices and watching the games. She also sat in on coaching sessions and built relationships with 10 of the players.

In terms of sheer desire to play, professional women players easily outscore their male counterparts. They have to buy their own uniforms and safety gear. Because pro football doesn’t pay the bills, they have to juggle jobs (and often family responsibilities) with team practice and fundraisers. They play on high school or college football fields, not in fancy sports arenas. Their fan base draws mostly from family and friends, and, except for a small burst when their team first forms, they get neither notice nor respect from the media in the sporting world.

Yet, still they play. Part of the game’s appeal probably lies in its “force without finesse,” the Merriam-Webster definition for the smashmouth football style favored by the Demolition and other women’s teams.

“Football lets women use their bodies in ways they’re not normally allowed to do,” Knapp said.

“Going up against an opponent and pushing -- that’s a feeling of empowerment.”

Demolition’s coaches reinforced that feeling by calling for and rewarding physical toughness.

“Pushing through injuries means being an ‘athlete,’ a term reserved for the elite players,” Knapp said. “The culture of football is very much about accepting injury.”

That toughness extended off the field. When thieves stole a couple of cars during a Demolition practice, one of the players went looking for them. She spotted one car at a nearby gas station. Two of the thieves saw her coming and ran off.

“The third one wasn’t so lucky,” Knapp recalled. “She held him up and pinned him against the vehicle until the police arrived.”

But while the players said they considered themselves “football players, not women playing football,” they’ve made some adjustments to the traditions, if not the game itself. Their coaches don’t just barge into the locker room, they announce themselves. Because men’s shoulder pads don’t accommodate women’s breasts, some Demolition players sought out newly introduced equipment made specifically for the female form. Many decided not to wear tailbone pads because they weren’t “flattering.” And players’ children frequently appeared on the field at practices and even some games.

No one knows where women’s football is headed, but with more than 1,300 girls playing high school ball in the 2007-08 school year, odds are they eventually will be no more novel than female soccer players. Just don’t expect it tomorrow, Knapp said.

“People tend to forget that for its first 30 years, the NFL ran in the red,” she noted.

“If it took men that long, you’ve got to know it’s going to take awhile for women’s football to get that kind of crowd.”