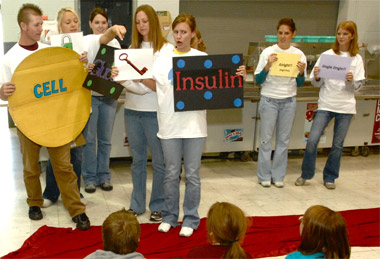

Playing along -- Nutrition students from Southern Illinois University Carbondale perform a skit about the role of insulin in the body during a visit to Cobden Elementary School. They wrote the skit as part of an educational program they created called “R. U. A. Healthy Kid?”, which aims to head off the development of diabetes in kids. (Photo by Steve Buhman) Download Photo Here

December 21, 2009

‘R.U.A. Healthy Kid?’ targets diabetes risk factors

CARBONDALE, Ill. -- A project aimed at heading off Type 2 diabetes in tweens and young teens looks to be on the right track, achieving statistically significant changes in body fat, muscle and snacking behavior.

“From a research perspective, we found out what works and what doesn’t with today’s middle school kids,” said Sharon L. Peterson, a registered dietitian and assistant professor of community nutrition at Southern Illinois University Carbondale.

Dubbed “R.U.A. Healthy Kid?”, the project began late in 2006 when Peterson, alarmed by reports of rising rates in children of what used to be called adult-onset diabetes, discussed the problem with a few of her students. The group decided to design a set of educational activities for kids most likely to develop the disease to get them moving, teach them about nutrition and help them feel better about themselves.

Peterson and her students tried out their new program the following year at Harrisburg Middle School, about an hour away from campus. More than half the school’s students agreed to undergo screening, which revealed that 22 percent of them had three or more of the five risk factors associated with the disease. Slightly less than half of those enrolled in the program.

Because it was so new, Peterson hadn’t expected much in the way of results. But in just three months, the Harrisburg kids decreased their percentages of body fat, increased their muscle mass, ate more vegetables and fruits, boosted their activity levels and increased their self-esteem.

“We were thrilled when we found significant changes -- enough to make us think there was something going on, to keep pushing, fix some of the problems and do it again,” she said.

Using feedback from the Harrisburg participants -- “They’re the experts on middle-school kids!” Peterson said -- she and her students made the wording of their screening survey more kid-friendly, developed activities and games with a higher “fun” score and tweaked their snack prep lessons.

“There’s no point in teaching kids how to make a mango salsa if there are no mangoes in their grocery stores or if mangoes cost $2 apiece,” Peterson said.

With updates complete, Peterson and her students took the program to grade schools in Vienna and Highland, screening late in 2008 and running the activities portion of the projects mostly in 2009. Again they found significant changes in body fat, muscle and snacking behavior. (They’re still analyzing the numbers on changes in activity levels and self-esteem.)

While Vienna and Highland are both in Southern Illinois, the two communities have only their small size and largely white make-up in common.

“They’re extremely different in terms of income, education and poverty levels,” Peterson said.

“We saw this as a real opportunity to do some comparisons between different socio-economic groups.”

Graduate student Lynn M. Cordes of Alton took charge of the comparisons and found differences from the get-go.

“At Vienna only 39 percent of those with two or more risk factors attended our program, where in Highland, it was nearly 79 percent,” she said.

“We did an after-school type program in Highland, so you could say that they were a captive audience, where in Vienna, it was on a Saturday, so parents had to take them. But later we did run a Saturday program in Highland, and attendance was still high.”

Highland families ate more meals at home, though childrens’ activities tended to interfere more than they did in Vienna. While Highland kids said they, unlike the Vienna group, had healthy snacks available at home, they went for the junk food anyway, in part because they liked the taste but also because it was easier.

“Junk food is in highly accessible form,” Cordes said. “You can have a whole pineapple sitting around, but kids won’t consume it because it’s not cut up and ready to go.”

Cordes also found media influenced snacking behavior in Highland.

“Kids said TV ads made junk foods look cool -- it was a very influential factor in their snack choices,” she said. “Ads didn’t have as much influence in Vienna.”

Because few studies have looked at Type 2 risk factors in white children -- and none focused on grade schoolers -- graduate student Sarah N. Sheffer of Carbondale homed in on Vienna, screening 299 youngsters, nearly 80 percent of the student population. She found 40 percent had a family history of the disease, 38 percent were overweight (higher than the national average), with nearly 18 percent of those morbidly obese. In addition, nine percent had high blood pressure.

Seventeen of the kids had three or more risk factors, including a 7- and 8-year-old. Noting that the state requires routine diabetes screening for sixth-graders, Sheffer pointed out that state screens would have caught only three of the 17 she found because they were the only sixth-graders in the group.

“In the case of the 7- and 8-year-old, a lot could happen before they reach sixth grade,” Sheffer said. “The onset of diabetes may have already occurred. Early intervention is key.”

Drawing on what they learned in Vienna and Highland, the next round of “R.U.A. Healthy Kid?” is already under way.

“We’ve taken our best stuff from the four Saturday workshops and boiled it down into an hour-and-a-half after-school program,” Peterson said.

They field-tested the new format at Cobden Elementary School in October, will test the tweaks with Carbondale eighth-graders early in 2010 and then will present the revamped program to middle schools in Carbondale, Rantoul and Urbana in the fall.

Peterson’s group also is working with folks at the University of Illinois to mesh SIUC’s diabetes intervention program with UIUC’s Web-based diabetes prevention modules.

“My students are writing up the lesson plans with notes on how long everything takes and what supplies are needed so someone else without any background could do this program,” Peterson said.

“My dream is to videotape some of our games and skits and have them on the Web site so that any kid in the country could visit, play along and learn.”