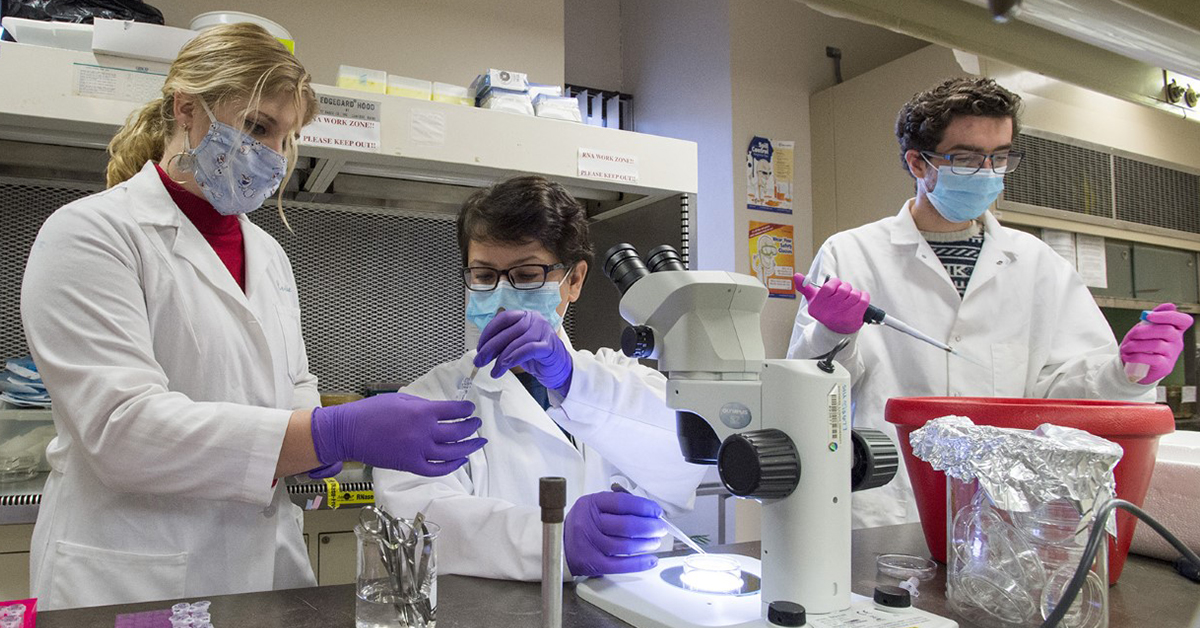

Morgan Burmeister, left, a senior in microbiology at Southern Illinois University Carbondale, works with Vjollca Konjufca, associate professor in the School of Biological Sciences, center, and Besmir Hyseni, a graduate student in micro and biochemical molecular biology. Konjufca recently published the results of a study that showed introducing a chlamydia vaccine orally and into the gut results in an immune response in the female reproductive tract. (Photo by Russell Bailey)

February 08, 2021

SIU research shows promise for vaccine against chlamydia in women

CARBONDALE, Ill. — A researcher at Southern Illinois University Carbondale has made key progress in creating a vaccine that could protect against the common sexually transmitted disease chlamydia and possibly other STDs. Vjollca Konjufca, associate professor in the School of Biological Sciences, recently published the results of a study that showed introducing a vaccine through the mouth and into the gut results in an immune response in the female reproductive tract.

A major threat

Chlamydia trachomatis bacteria typically wreak havoc on younger people. If left untreated, chlamydial infections may lead to the development of pelvic inflammatory disease, chronic pelvic pain, hydrosalpinx (blocked fallopian tube), endometriosis and infertility. Women with chlamydial infections are at a higher risk for acquiring HIV infections and for developing HPV-associated cervical cancer.

More than 1.7 million cases were reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in 2018, making it the leading bacterial sexually transmitted infection. But health officials estimate the actual number of cases in United States was almost 2.9 million that year.

About two-thirds of those carrying the disease are not aware of it, meaning it is often left untreated and spreads easily.

Drug treatment is available, but reinfection is common, leading the CDC to recommend post-treatment testing. The large scope of the public health problem has led the research community to actively pursue improved treatment approaches and prevention.

The search for a vaccine

Currently, there is no licensed vaccine available to prevent infections of chlamydia, and other than the one for human papillomavirus (HPV), vaccines for sexually transmitted infections don’t exist.

Currently, there is no licensed vaccine available to prevent infections of chlamydia, and other than the one for human papillomavirus (HPV), vaccines for sexually transmitted infections don’t exist.

“One of the main reasons for this lack of success in developing mucosal vaccines against STIs is that we do not fully understand how to best induce immunity in the female reproductive tract,” Konjufca said.

Biologists in recent years have become more and more convinced that healthy gut bacteria are key to a host of bodily functions, including immune responses. Previous work showed that orally administering mice with live C. trachomatis did result in vaginal and reproductive protection against the disease, though it had not precisely identified the biological mechanism that caused this result.

Konjufca’s work, funded by the National Institutes of Health and the National Science Foundation, may have uncovered how that process works.

“Our findings are important because for the first time we show that antibody secretion in the female reproductive tract can be induced by oral immunization,” she said.

Moreover, the research showed that antibodies secreted in the mucosa of the female reproductive tract neutralize C. trachomatis and limit its ability to infect the upper reproductive tract such as the uterus, ovaries and oviducts, thus preventing long-term pathology.

Unlocking the secret?

In her study, mice also received a dose of live or killed C. trachomatis orally, which then triggered the expected antibody response in the reproductive tract, which is critical for protection against the disease. But Konjufca also identified the gut mucosa – specifically the gut-associated lymphoid tissue – as the key site for inducing the response, as well as the fact that inactive C. trachomatis alone can be used.

“The study showed that infection with a living pathogen is not necessary for immunization,” Konjufca said.

In concert with the mouse model, Konjufca’s lab used an array of experimental techniques to evaluate the immune responses after the dose and to evaluate the protection it provided. Such techniques included imaging, molecular biology and tissue culturing, as well as immunology techniques such as cloning, gene expression, protein purification and antibody measurements, among others.

A gateway to more?

Konjufca is continuing work to more thoroughly identify the mechanisms that allow the immune response to transfer from one mucosal site – such as the digestive tract – to another, such as female reproductive tract.

“We hope that this work will focus the research on the development of oral vaccines to target not only Chlamydia trachomatis but also other sexually transmitted pathogens,” Konjufca said.