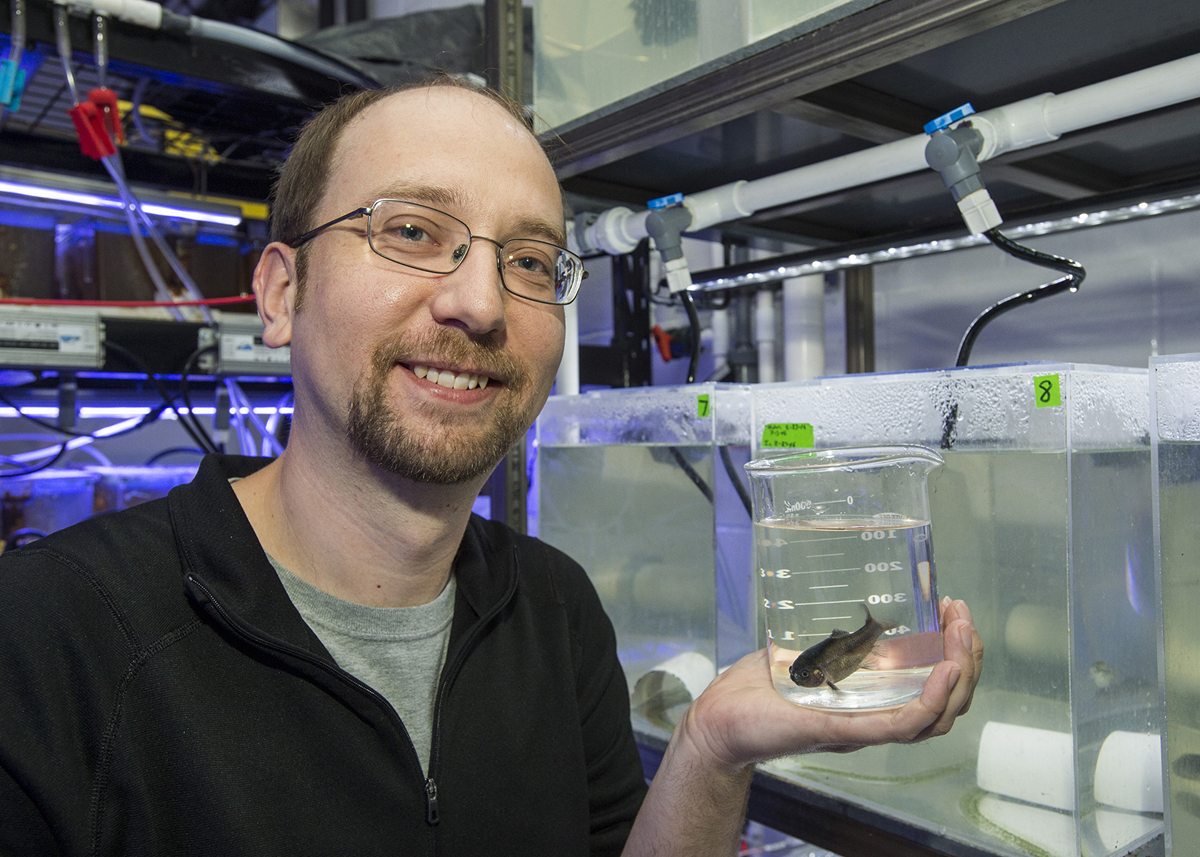

David Coulter, a post-doctoral researcher at Southern Illinois University Carbondale, holds a fathead minnow at SIU’s Center for Fisheries, Aquaculture, and Aquatic Sciences. A meticulous, two-year study by a team of SIU researchers found that PCBs in the environment make the male of the species into poor parents. The research, recently published in American Chemical Society’s Environmental Science & Technology journal, found that lifelong exposure to PCBs led to decreased nurturing behavior by male fathead minnows and lower survival rates of their offspring. (Photo by Russell Bailey)

August 22, 2019

Two-year study by SIU researchers finds PCBs make minnows into bad dads

CARBONDALE, Ill. — A mother’s nurturing of her offspring is a well-known story in the natural world. But when it comes to fish, it’s dad who is often tasked with the care of young ones.

One legacy of a once popular industrial chemical, however, appears to include a negative effect on this instinct in a certain fish species, according to a meticulous and time-consuming study by researchers at Southern Illinois University Carbondale.

Their findings, recently published in the American Chemical Society’s Environmental Science & Technology journal, found that lifelong exposure to polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) led to decreased nurturing behavior by male fathead minnows and lower survival rates of their offspring.

David Coulter, a post-doctoral researcher at SIU, is the lead author on the article, which also includes a team of SIU and Purdue University researchers. The study took two years and involved countless hours of laboratory work at SIU’s Center for Fisheries, Aquaculture, and Aquatic Sciences.

A troubling legacy

PCBs were once produced widely for use in industrial applications. Their use was banned in the 1970s because of health and environmental concerns. Even so, PCBs remain a worldwide problem because of their resiliency, which has allowed them to hang around in the environment for decades.

Animals, such as fish, mainly become contaminated with PCBs by eating food that contains them. The contamination is known to create physiological changes in animals.

“We wanted to understand whether PCBs reduce the ability of male fish – in species where only fathers care for young – to successfully produce offspring and, if so, identify which reproductive processes might lead to this result,” Coulter said.

Male fish play critical role

In many animals, fathers and mothers both contribute to producing healthy offspring by creating suitable nests, fending off predators and tending to offspring, Coulter said. Most research, however, focuses only on mothers’ importance for offspring success.

But fish are different.

In many species, including popular sport fish such as bluegill and largemouth bass, for example, males are influential caregivers for offspring, and their ability to successfully reproduce and care for young can affect the entire population.

“In some fish species only the fathers care for their offspring after birth,” Coulter said. “This makes the father’s role quite important for maintaining a healthy population since the number of new adults each year depends on how well fathers can care for their young.”

Careful, meticulous challenges

Working with fellow SIU researchers Kara Huff Hartz, James Garvey, and Michael Lydy, as well as SIU undergraduate researcher Amy Turlington, Coulter raised a group of fathead minnows, dividing them into experimental groups and a control group. The experimental groups received PCB-contaminated worms – also raised from scratch at an SIU lab – as a food starting when they were one month old. The control group received PCB-free worms.

This portion of the study took about seven months, and challenges reigned all along the way. Each day involved using forceps to pick worms out of the PCB-contaminated sediment where they were raised, feeding worms to fish, cleaning fish tanks and monitoring tank water quality. Losing the fish to a die-off at any point would have cost the team months of work. Record-keeping and measurements of various kinds were the order of the day, as well.

Seven months later, however, the team had cohorts of fish ready to breed for the second half of the experiment.

Watching, measuring results

Now mature, the researchers placed males with uncontaminated females and allowed them to breed, videotaping breeding behaviors and counting the number of live offspring each male produced and kept alive.

Later on, the researchers dissected males to measure hormone production and testicular and body development. They also took a large number of measurements to determine how the PCBs specifically affected the minnows’ ability to reproduce.

They analyzed brain tissue to measure effects on genes that produce reproductive hormones, testicular development at a cellular level, physical appearance of males, male breeding behavior and offspring survival.

“Processing these samples and analyzing and interpreting the data was quite time-consuming, about another year or so. But collaborating with an excellent research team allowed us to overcome the challenges,” Coulter said.

Troubling findings

The team found PCBs changed male appearances to be more like females, although it did not affect their ability to attract females and get them to lay eggs in their nest. Once the eggs were laid, however, the males dosed with PCBs were less attentive fathers, spending longer periods away from their nests. Even when they were present at the nest, they tended less often to their offspring. The behaviors appear to have led to the reduction in offspring survival observed by the researchers.

Researchers estimated that such a rate of survival, if experienced in the wild, would, over time, lead to a reduced number of adults in the entire population, although more work would be needed to confirm that hypothesis.

Understanding the degree to which reproduction is inhibited by PCBs and how this occurs can help scientists enhance models that predict how fish populations respond to human environmental disturbance. That, in turn, can help wildlife managers create plans aimed at maintaining healthy populations.

“Maintaining healthy fish populations is a global natural resources priority, as many societies rely on fishing industries for economic purposes and for subsistence,” Coulter said. “PCBs will remain a problem affecting many of these species, and our findings shed light on processes that are occurring in the wild.”