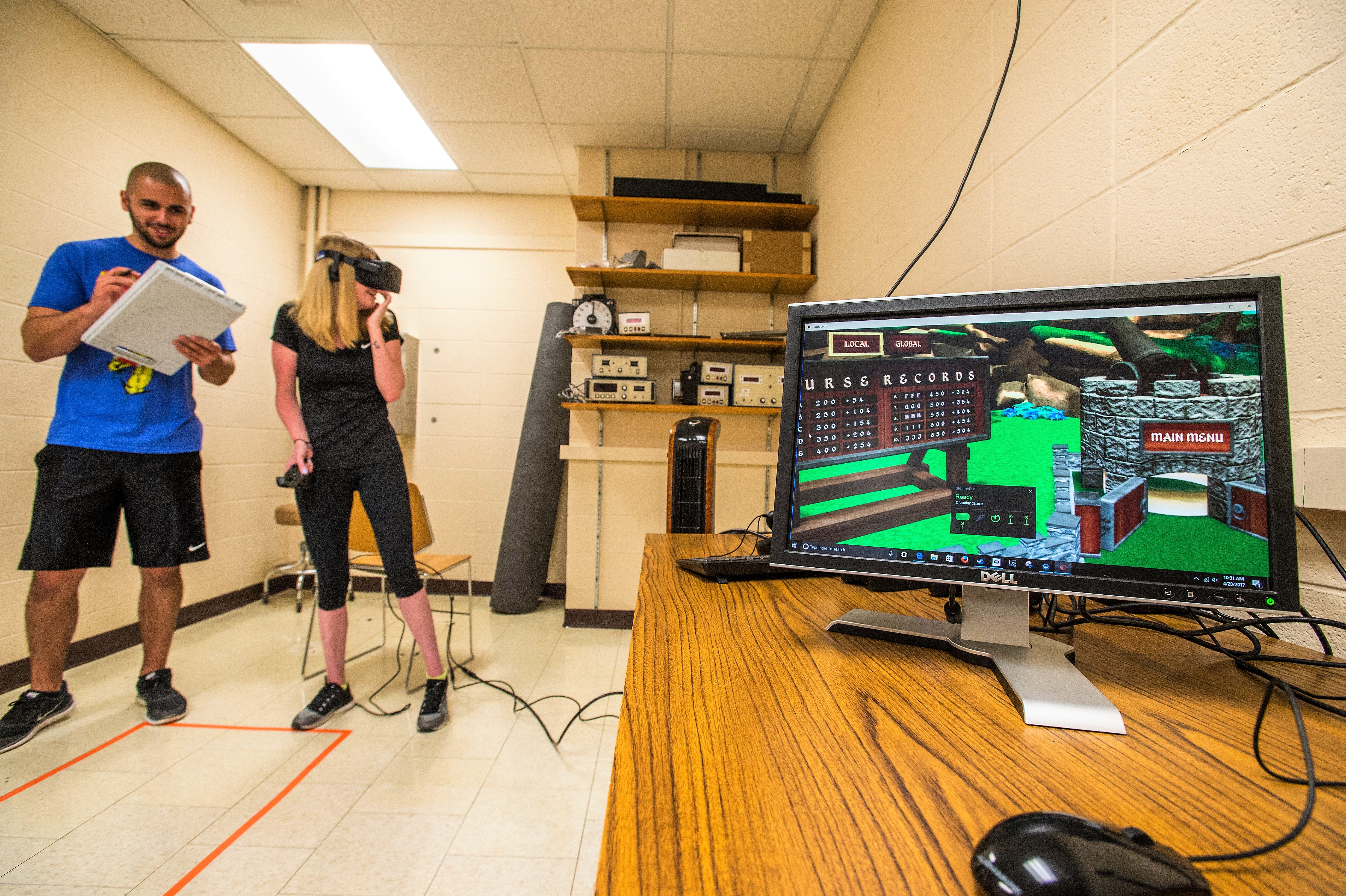

Koleton Cochran, left, a senior exercise science major from Decatur, observes Katy Ovington, a master’s student in kinesiology from Durham, England, react as she practices golf via virtual reality. Cochran and Jared Porter, associate professor of kinesiology and director of the Motor Behavior Lab, are conducting research to determine if simulated virtual reality practice equates to improvement in skills just like real-life practice does. (Photo by Steve Buhman)

June 02, 2017

Study explores practice in a virtual environment

CARBONDALE, Ill. – Practice makes perfect, so the old adage goes. But, does it matter what kind of practice you get?

Katy Ovington lined up her shot and putted. But instead of a club, she held an electronic hand-piece. The ball and putting green were visible only through the virtual reality goggles she wore or on a nearby computer screen in Southern Illinois University Carbondale’s Motor Behavior Lab.

She was “practicing” golf via virtual reality in conjunction with a research project being conducted by Jared Porter, associate professor of kinesiology and Motor Behavior Lab director, and Koleton Cochran, a senior exercise science major from Decatur. Ovington, a master’s student in kinesiology from Durham, England, was so immersed in the experience that when she “moved” through the virtual environment to get to her ball to take the next swing, she visibly cringed and took a step backwards in response to “walking” into a virtual wall.

“Our research explores how humans learn and perform motor skills, and how their learning translates to movement,” Cochran said. “If you practice in fake reality, how does the brain perceive it? Does it still learn? That’s what we wanted to find out.”

That’s why Porter and Cochran are studying whether practice in a virtual environment translates into improved performance just like real-life practice does. Over the course of several months, 68 participants were tested in the lab. Each was given a 10-shot “pre-test” on a putting green and their scores were recorded. Then, half of the group practiced golf in the lab on three miniature-golf style holes of varying difficulty. Their counterparts practiced as well, exclusively on a set of virtually identical virtual reality holes created by Cochran utilizing the Oculus Rift system and Cloudlands VR Minigolf.

The equipment and software were purchased through a grant Cochran received from the competitive REACH program, which funds SIU undergraduate research or creative activity projects. He designed the virtual practice field to mimic the real-life setup as much as possible. Indeed, with a flick of the wrist, the golf club swings and sends the virtual ball flying.

“I was very pleasantly surprised at how good and accurate it is,” Porter said.

Each group got 50 practice swings. The only difference was their practice environment within the lab. For some, it was a metal club, a golf ball and a putting green. For others, it was an entirely computer-generated course. Helping with the research were Sean Gloss, an exercise science master’s student from West Chicago; Emily Stewart, a senior exercise science and physical therapist assistant major from Marion; and Bailey Smithpeters, a senior communication disorders and sciences student from Harrisburg.

Afterward, all of the study participants were re-tested, taking the same 10 shots they took in the pre-test. The scores were tabulated and compared.

“You couldn’t tell the difference. It’s pretty profound,” Cochran said. “There doesn’t seem to be any difference and from our perspective, that’s a pretty neat finding.”

“In short, both groups showed similar improvement in golf-putting performance through the duration of the study,” Porter said. “At the end of the study, the two groups were nearly identical with the virtual reality group having an average putting score of 6.82 and the real-life practice group having an average score of 6.89. It is interesting to note though, that the virtual reality group actually showed a greater increase in putting performance compared to the real-life putting group through the course of the study, with an average accuracy improvement of 18 percent for the virtual-reality group compared to an 11 percent improvement for the real-life putting group.”

Improving golf games wasn’t really the goal of the research though. Cochran wonders if medical professionals could learn to perform physical therapy or other medical procedures via virtual practice as effectively as they could with real-life training. Can a therapist practice physical therapy skills or a physician train for surgical procedures electronically rather than with living humans or cadavers? While that hasn’t been tested yet, Cochran and Porter think their research indicates it’s quite possibly just as effective. And that’s not all.

“Anecdotally, people seem to have more fun with the virtual training, and when something is more enjoyable, people are more likely to practice more which would also likely lead to greater improvement in skills,” Porter said.

They also see possible applications for the military, the airline industry, and for carpentry and other types of skilled labor.

“There are so many ideas for possible applications. The sky is the limit,” Porter said.

The research will continue in the fall. In addition to pursuing other applications for the study of virtual versus real-life practice, plans call for a kinematic study to investigate movement characteristics involved in golfing. The study will utilize video recordings made during the initial study. Cochran and Porter hope to publish their work as well.