A group of faculty at Southern Illinois University recently received a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities that will help broaden the perspective of students who are involved in STEM studies by attracting them toward the humanities. The effort also will result in a new, unique minor in ancient practices, which will help students appreciate and apply the wisdom of such classical cultures from around the world.

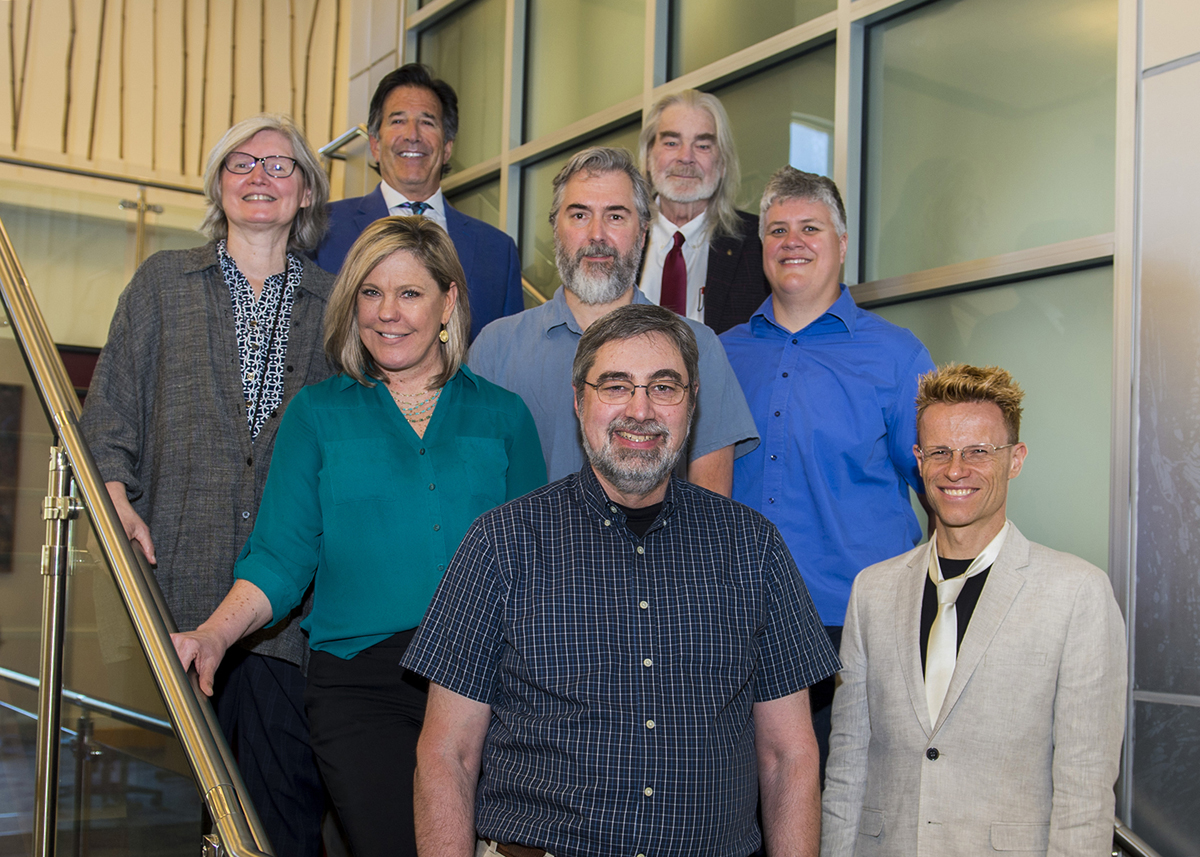

SIU faculty involved in the effort are, bottom row left to right: Ken Anderson, professor geology, co-principal investigator; and Mont Allen, assistant professor of classics and art history in the Department of Languages, Cultures and International Trade, principal investigator. Middle row: Frances Harackiewicz, professor of electrical and computer engineering; Lynn Gill, senior lecturer of animal science, food and nutrition; Matthew McCarroll, professor of chemistry and director of the Fermentation Science Institute; Gretchen Dabbs, associate professor of anthropology. Top row: Robert Hahn, professor of philosophy and Jon Davey, professor of architecture. (Photo by Russell Bailey)

April 19, 2019

NEH grant will combine STEM, humanities in new minor at SIU

Modern computers and mathematical modeling can precisely describe the shape, size and color of a tulip. Chemical-sniffing “noses” might even describe its aroma.

But none of these high-tech approaches can capture the way it feels to see the flowers emerge as spring reanimates the land following a long winter, let alone articulate what it has meant to cultures present and past. That’s a job for poets and essayists, for philosophers and historians, for classicists and such. That’s a job, in short, for the humanities.

Ancient people, new minor

A group of faculty at Southern Illinois University Carbondale recently received a grant that will help broaden the perspective of students who are involved in objective disciplines – such as science, engineering and technology and mathematics – by attracting them toward the humanities. The effort also will result in a new, unique minor in ancient practices, which will help students appreciate and apply the wisdom of such classical cultures from around the world.

Starting this summer, the Humanities Connections Grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities will bring $100,000 to SIU to formulate a few new, highly interdisciplinary courses to complete the offerings for the minor. The grant, which was one of only four funded nationwide by the NEH out of 51 proposals, will run for three years.

The minor officially won’t be available until next fall, but once it’s approved, current students can apply courses they are taking right now to the minor. To earn the ancient practices minor, students will take three lecture courses – nine credit hours – from among a diverse selection of those offered by the eight participating faculty, as well as a capstone project, typically as seniors. The capstone project will be from a subject within their major, but on a topic that is relevant ancient practices. For instance, an engineering student might choose to build a catapult, or geology student might conduct a project on optical geology, studying so-called “sun stones” the Vikings used to navigate on the ocean.

The program will emphasize learning through experience and may include a study abroad component, as well.

Diverse group of faculty spearhead effort

Mont Allen, assistant professor of classics and art history in the Department of Languages, Cultures and International Trade, is leading the effort as its principal investigator, along with Ken Anderson, professor geology, who is the co-principal investigator on the grant.

Along with Allen and Anderson, six other faculty from diverse backgrounds will ensure program’s interdisciplinary flavor. They include: Frances Harackiewicz, professor of electrical and computer engineering; Gretchen Dabbs, associate professor of anthropology; Lynn Gill, senior lecturer of animal science, food and nutrition; Matthew McCarroll, professor of chemistry and director of the Fermentation Science Institute; Jon Davey, professor of architecture; and Robert Hahn, professor of philosophy.

Balancing STEM with humanities

These days, with so much emphasis placed on so-called STEM education, the humanities and the important lessons it teaches about values, the human condition and culture can get lost in the shuffle. The ancient world, where the roots of such studies lie, still has much to teach us, Allen said.

“For one thing, it’s a reminder that the more things change, the more they stay the same with humans. We share a deep continuity with all humans back through time,” he said. “Also, and maybe diametrically opposed to that notion, is how radically different our approach to the world is and their approach to it was, as well as their perceptions of their environment and the ways they interacted with it.”

The ancient Greeks, for instance, made almost no distinction between making an everyday appliance, such as a cup or a bowl, and a work of art. They used the same word for both: “techne,” which essentially meant the act of making something.

“That became the root of our word, ‘technology,’” Allen said, “but the word could just have be translated as ‘art-ology.’’’

Humanities develop important skills

Anderson said studying the humanities develops skill sets and habits of mind that society needs and employers seek out, even among workers in technical fields.

“The critical and creative thinking, writing and communication skills, these are valued by all disciplines,” Anderson said. “Students who get only technical training don’t necessarily develop such skills as well as they could and should.”

Same challenges, different millennia

The effort also is aimed at showing students how the ancients approached the day-to-day problems and challenges of living without the vast array of technology and machinery available to today’s societies.

“People back then had to solve all the same problems we do: food, shelter and such. And they solved them with very clever solutions,” Anderson said. “Two, three, four thousand years on, they are still impressing us.”

From the pyramids to the acropolis to basic hygiene and even brewing beer, the effort seeks for students to understand the creative thinking that arose from the ancients’ understanding of their world, Allen said.

“I would like our students to be really astonished and gobsmacked with what they learn,” he said. “How did the Romans make concrete? How did they make concrete that would set underwater, which allowed them to make the first massive artificial harbors?”

Historical and cultural context is key, as well, Allen said.

“We want students to get a sense for how such advancements would have resonated in the culture back then,” he said. “So it’s essential to understand Roman social structure, and how it was they were able to do things, such as press gangs of slaves into service.”

Wisdom for today’s world

Such lessons are critically applicable in today’s world, Anderson said, where the danger exists of societies losing appreciation for culture, the fine arts and philosophy while the technologically savvy gain untoward power over those who are less so.

A balance is needed, he said.

“Physics makes the world go ‘round, it’s true. But art, music, culture – these make it worth the ride,” Anderson said. “By the same token, if you’re a humanist and you think your cell phone works by magic, you’re making a serious mistake.”