October 19, 2011

Library’s rare 1597 atlas now available to public

CARBONDALE, Ill. -- Once in a while, someone actually discovers buried treasure.

It happened recently at Southern Illinois University Carbondale’s Morris Library. Ann Myers, Special Collections cataloger, was sorting through and cataloguing items in the library’s Special Collections when she discovered a rare atlas, one of only four known to exist in the world.

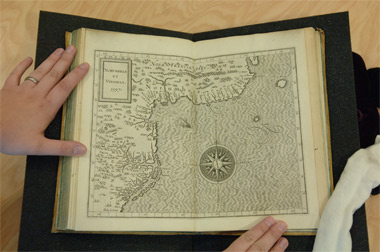

Published in 1597 in Louvain, Belgium, by Jean Bogard, “Descriptionis Ptolemaicae augmentum, siue Occidentis notitia” is the first atlas featuring maps of the new world. The book, about a foot high and nine inches wide, includes 19 double-sided pages with engraved maps of North and South America. Myers said the black and white drawings are very detailed in some areas, including the Caribbean Islands and the areas around Florida, Virginia, Greenland and Canada’s eastern coast.

“There is nothing for the interior of North America, though, and I suspect the interior of South America is not entirely accurate. It does depict the west coast of North America, including California,” Myers said.

She said the atlas is significant for a number of reasons, particularly in that it is the first edition of the first issue of the first atlas of the Americas and it was actually a companion to Ptolemy’s “Geography.” In fact, according to Myers, a very rough translation of the volume’s name is “An Addition to Ptolemy’s Description, or, Knowledge of the West.”

Ptolemy was a second century Greek astronomer who wrote extensively about geography, including instructions for three methods of map projection and explanations of latitude and longitude. His work circulated in a manuscript form and later, after the invention of print methods, in that format. Widely influential, his writings included an exaggerated estimate of Asia’s size that helped inspire Christopher Columbus’s voyage.

According to Myers, authorities largely credit this atlas with dispelling numerous misconceptions about the new world.

“For example, from about 1510 through the 1700s, many mapmakers depicted California as an island, separated from the continent by the Gulf of California. The map in this volume clearly shows California as part of the mainland,” she said.

While the atlas dispelled many myths, its maps are proof that there were still many mysteries remaining with regard to the Americas.

“By 1597, there had been considerable exploration of the east coast of Canada in search of the Northwest Passage and there had been a failed colonial settlement in Virginia at Roanoke Island (now in North Carolina), but the area in between had not been charted in detail. This vagueness is evident on the maps in the atlas. There is a label for Chesapeake Bay, although it is not geographically accurate, and there is no sign of Cape Cod or other details of the coastline,” Myers said.

“There is also a region in what is now New England labeled Norumbega, and a city with the same name. Norumbega was a legendary settlement, believed to exist in northeastern North America. French navigator Jean Allefonsce claimed in 1542 that he had floated south from Newfoundland and discovered a city called Norumbega. He described it as being a large, rich, native city, full of furs and other riches. The name frequently appeared on European maps for years and although scholars attempted up through the 1800s to show where the original city was, no one has ever proved its existence,” she added.

The text in the atlas, by Corneille Wytfliet, a mapmaker of the era, is in Latin. Library officials believe that the Huntington Library, the University of Minnesota and the John Carter Brown Library hold the only other known copies of this issue and edition.

The original source for the Morris Library copy of the book is not certain but Myers said it was most likely a gift from Dr. Harley K. Croessmann, a Du Quoin optometrist. Croessmann gifted the library with the bulk of its James Joyce Collection, including the manuscripts, as well as about half of its Early Printed Book Collection. Croessmann, who died in 1962, donated a large collection to the library in the 1950s.

The 1597 atlas is part of the library’s Early Printed Book Collection and efforts began to catalog that collection in 2008, leading to the “rediscovery” of the 400-year-old atlas, Myers said. She said although an inventory listed the book, it is now accessible to the public for the first time. Anyone may view it by visiting the Morris Library Special Collections reading room and requesting the book.

She also noted that cataloguing of the entire collection the atlas is part of is now complete so people can search the library catalog for “Early Printed Book Collection” and find the records for the more than 500 books the collection includes. Look online at http://tinyurl.com/3swk87y for details.

For more information about this atlas or Morris Library and all it has to offer, contact the library at 618/453-2818 or visit the website at http://lib.siu.edu/.