October 18, 2005

New book dispels myth that rock 'n' roll is dead

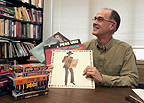

CARBONDALE, Ill. -- While adages are known for their historical longevity, that doesn't mean they are true.One familiar refrain - that rock ‘n' roll is dead - is a myth dating back five decades, according to Kevin J.H. Dettmar, an English professor at Southern Illinois University Carbondale.

"It seems as if there is this continual cycle of death and rebirth. And what gets interpreted as the death throes of rock can be seen from another perspective or with hindsight as rock just changing into something else," said Dettmar, author of the upcoming book, "Is Rock Dead?"

Routledge will publish the approximate 200-page book in late December.

The book isn't primarily about the music itself, Dettmar explains, but "about the way we talk about and write about rock ‘n' roll and why we seem to feel this need to keep declaring it dead."

Dettmar's interest in how popular music moves through the culture was sparked after reading what he labels a "snotty, smug review" of the Radiohead album, "Kid A", by British novelist Nick Hornby in the New Yorker magazine several years ago. That review, in which Dettmar says Hornby decided no important new rock ‘n' roll would be made and the "rock era was over," triggered his memories of other writers who similarly offered that view.

Dettmar's research covering 50 years of popular media and scholarly writings explores the different ways and reasons that each generation declares that rock ‘n' roll is on life-support, or dead.

The book also examines how rock musicians in varying ways "dance on their own graves" with songs that declare rock ‘n' roll is dead.

Dettmar says rock ‘n' roll is most often attacked during moments of national crisis: fears of communism and greater teen independence in the 1950s; anti-war movements in the late 1960s and early 1970s; concerns with lyrics and formation of the Parents Music Resource Center in the mid-1980s; or the emergence of rap and hip-hop music today.

"If you look carefully at those moments, you'll find that we are not dealing with the real issues," he said. "We are displacing a lot of nervousness, insecurity or anxiety onto rock ‘n' roll. It becomes a scapegoat for bigger issues and bigger problems."

One of the first declarations of rock ‘n' roll's death came in September 1956 with the release of "The Death of Rock and Roll," by Maddox Brothers and Rose, a white rockabilly group that performed at Louisiana Hayride shows with Elvis Presley. The song is a cover of Ray Charles' song, "I Got a Woman."

When writing about rock ‘n' roll performances, journalists of the time also focused on the music's "hysteria" effect on its audiences. The descriptions make it "pretty striking how angry or fearful people really were," Dettmar said. One article of the day predicted that Presley would be the death of rock ‘n' roll because he had no talent and couldn't sing.

The book is critical of rock music critics – particularly those from the baby boomer generation who are Dettmar's age or a little older, whom he labels "Rock Curmudgeons" or "Boomer Triumphalists." He views many critics as "territorial and defensive" concerning the music they initially grew up with.

"These critics pretend to be upset about the death of rock, but in fact I would argue they are involved in trying to kill off rock; they would rather see it dead because then it's theirs forever," he said.

"A lot of those people now are writing about the death of rock; it's a sort of mid-life crisis – an inability to deal with their own ceasing to be at the cultural center of what is going on," he said.

Dettmar hopes the book convinces readers that it is "silly" to keep talking about the death of rock ‘n' roll.

"When people are saying ‘any day now, tomorrow, or the day after tomorrow' that rock is going to die and 50 years later it hasn't happened – maybe it's time to tell a different story – to maybe look at the challenge that rock presents and look at it a little more creatively," he said.

That includes today's current debate involving whether rap and hip-hop fit into the rock ‘n' roll genre. Dettmar believes people need to stop making "narrow, fussy distinctions," of what rock is – and isn't.

"To me, that kind of ignores how much the two musics have in common," he said. "There is no hip-hop without rock. They are more similar than they are different."

The issue isn't that rock music is dying but that it keeps reinventing itself, Dettmar said.

"Every time a kid discovers a record and it picks him up and makes his day," he said. "Every time a person gets excited about a new record or even an old record gets rediscovered, rock gets reborn. It's not a static thing."

Providing a healthy academic environment that values the innovations and results of research, scholarly and creative activity is among the goals of Southern at 150: Building Excellence Through Commitment, the blueprint the University is following as it approaches its 150th anniversary in 2019.

(Caption: Exploring the myth of rock ‘n’ roll’s death – Kevin J.H. Dettmar, an English professor at Southern Illinois University Carbondale, has written a book that examines why the myth about the death of rock ‘n’ roll continues five decades after its emergence. Dettmar’s book, “Is Rock Dead,” is due to be published in late December.)

Photo by Steve Buhman